John Reischman Discography

John Reischman Web site

CoMando Guest of the Week

Children's Mandolin Roundtable

Instruments

A-Style Mandolin

F-Style Mandolin

Mandola and Mandocello

Vintage Dealer's Roundtable

Saturday Morning Luthier's Corner

Mandolin Builder's Super Summit

The Virzi Vortex

Mandolin Buyer's Guide

Music Apps

The Genius of Lloyd Loar

Mandozine Gallery

Vintage Grass Valley Photos

Articles

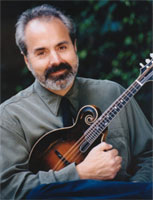

John Reischman

John Reischman is one of the top-ranked contemporary mandolin players, revered for his exquisite taste, tone, and ability to play genres ranging from bluegrass to jazz to hot swing to Latin and beyond. He toured and recorded for many years with California's eclectic Good Ol' Persons and helped define the groundbreaking "new acoustic" instrumental scene as a member of the Tony Rice Unit in the early '80s.

John Reischman is one of the top-ranked contemporary mandolin players, revered for his exquisite taste, tone, and ability to play genres ranging from bluegrass to jazz to hot swing to Latin and beyond. He toured and recorded for many years with California's eclectic Good Ol' Persons and helped define the groundbreaking "new acoustic" instrumental scene as a member of the Tony Rice Unit in the early '80s.

John's debut solo album, North of the Border (Rounder) showcases his broad musical depth and composing skills in a variety of musical settings. In the fall of '98, John released an exciting new duet album with renowned Seattle acoustic guitarist John Miller, entitled The Singing Moon (Corvus). It features mostly original instrumentals inspired by Latin and jazz, creating a new world musical potpourri that defines its own territory. The summer of '99 brings us Up in the Woods, his all-original album that marks a return to his bluegrass roots.

John Reischman has also lent his distinctive signature - sophisticated, graceful and powerful - to an ever-growing list of recordings by such highly regarded musicians as Todd Phillips, Scott Nygaard, Kate MacKenzie and Susan Crowe, and tours frequently with a range of dynamic performers including John Miller, Grammy nominee Kate MacKenzie, Juno nominee Susan Crowe, Bay Area star Kathy Kallick, and Vancouver bands Bluegrass Signal and Gypsalero.

Born in Ukiah, California in 1955, John first played the guitar at the age of 12 and explored fingerpicking and blues styles before discovering the mandolin at age 17. "After a while it was obvious that I was going to go with the mandolin," says John, who drew inspiration from the playing of bluegrass patriarch Bill Monroe and "new acoustic" pioneers David Grisman and Sam Bush.

In addition to his love of bluegrass, John developed an interest in swing and jazz through his exposure to the music of Django Reinhardt, Jethro Burns and Tiny Moore. John also explored the haunting Latin sounds of Brazilian choro and Puerto Rican jibaro music. His warm, resonant tone, melodic sophistication and clean, strong execution have developed through the years from these many musical sources.

In 1978, John joined the Good Ol' Persons, a San Francisco Bay-area group playing traditional and contemporary bluegrass and acoustic music. With an emphasis on original material and a willingness to push the boundaries of traditional bluegrass, the band was the perfect forum for John to hone the many styles he'd cultivated. John also began to exercise his skills as a composer and soon caught the attention of guitarist extraordinaire Tony Rice, who invited John to tour and record with the cutting-edge Tony Rice Unit.

Here, John had an opportunity to further refine his seamless technique and improvisational skills. "A lot of mandolin players at that point were just sort of doing the basic percussive chop," says John. "I was trying to pay more attention to getting the full voicing, the harmonic aspect." The music was exacting, polished and progressive. A concert might include pieces by Miles Davis and Earl Klugh in addition to vibrant originals by Tony and John. After four years with both groups, the increasingly popular Good Ol' Persons became John's primary outlet for the remainder of the '80s.

John, who lives in Vancouver, Canada, maintains a busy schedule of performing and recording in a typically wide range of musical configurations. The John Reischman / John Miller duo perform multi-dimensional original music including jazz, Latin, Tin Pan Alley and other influences, with delightful interplay between Reischman's soaring melody lines and Miller's unique rhythmic finger-style guitar playing.

John appeared on the 1996 Grammy Award winner for best bluegrass album, True Life Blues: The Music of Bill Monroe. He also played on Kate MacKenzie's 1997 Grammy Award nominated bluegrass album, The Age of Innocence, and Susan Crowe's Juno-nominated album This Far From Home.

John has also toured with the Rounder Banjo Extravaganza, which featured Tony Trischka, Tom Adams, Tony Furtado and John Hickman, and with ace guitar flatpicker David Grier. As a session player, John has highlighted a number of albums by such names as Grammy Award winner Todd Phillips, Tony Furtado, Sarah Elizabeth Campbell, Scott Nygaard, Cindy Church, and Raffi.

John's current main performance project is with The Jaybirds. Joining John in the Jaybirds are four acoustic players renowned in their own right: Jim Nunally, guitarist, vocalist, composer and producer from the San Francisco Bay Area; Chilliwack, British Columbia's Trisha Gagnon on bass and vocals; Seattle's Nick Hornbuckle on 5-string banjo and Spokane's Greg Spatz on fiddle.

John tours frequently with Susan Crowe, Kate MacKenzie and Kathy Kallick, and in the Vancouver area, he performs with the hot swing band Gypsalero, and with Brazilian multi-instrumentalist Celso Machado and Puerto Rican percussionist Sal Ferreras. John is a familiar presence at bluegrass, jazz and folk festivals. In addition, he is in demand as a mandolin teacher and conducts workshops throughout the United States and Canada.

Q1

Q - One of the many things I admire about your playing is your seamless

transition from tremolo passages to single note runs and back again. What advice would you give a student who does both OK but stumbles when

transitioning between each technique?

A - I am glad that you appreciate that aspect of my playing because it is

something I have worked on and still find challenging. One thing I do is practice with a metronome. What I recommend is starting at 100 bpm and playing a triplet pattern over two beats, so the pattern you end up with over four beats is : down up down up down up. The second set of triplets will start with an up stroke, so I always keep this a two triplet pattern. When you start this slow it doesn't sound like tremolo. Keep it even sounding and gradually increase the tempo.You can emphasize the first of the six pick strokes to stay rhythmically grounded because that first down stroke will be on the beat. It will create a 6/8 feel. When you get to 200 pbm it should sound like tremolo. You can keep the emphasis on the first beat or make it sound completely even. I always end the tremolo pattern with a down stroke. I find this way of approaching tremolo especially effective for slow to medium tempo waltzes like Lonesome Moonlight Waltz.

Q2

Q - Why do you like to play a wide range of musical styles?

What effect does this have on your bluegrass playing?

Who are you inspirations that are not bluegrass or mandolin

players?

A - I do like many styles of music and some have inspired me enough to try and learn something about them. I played guitar when I was a teenager. I played various folk tunes, rock and roll, and blues. In fact, Robben Ford and I grew up in the same town. He was in a high school band with my next door neighbor and I would go over and listen to their rehersals. They were a really good Chicago style blues band and I count that as one of my first strong musical inspirations.

Bluegrass is the first music I tried to play on the mandolin. I thought it was really exciting music and the idea of an acoustic string group really appealed to me. Eventually I heard Django Reinhardt and thought he was just amazing and, again, the context was an acoustic string ensemble. A little later I found out about Jethro who was playing this same style on the mandolin!

A fan of The Good Ol' Persons gave me a tape of Puerto Rican Jibaro music. I thought this was great stuff, especially the rhythmic phrasing of the cuatro players, and the singing was very passionate. I also started listening to a similar Cuban style performed by groups like Cuarteto Patria. Various Latin styles had appealed to me before this, but this music was acoustic. I became aware of Brazilian Choro music shortly after this, and it naturally appealed to me because it featured the mandolin. At one time, especially when I played with The Good Ol' Persons, these other styles had an affect on my bluegrass playing. That band was my only musical outlet for a long time, and it was the context for me to express these various musical interests. Playing with Tony Rice was a similar situation. To play that music you needed to have a Bluegrass background but also a knowledge of Jazz harmony. Now I have two main musical outlets, my duo with John Miller, and The

Jaybirds. In the Jaybirds I try to play in a fairly traditional style and still remain creative. With John Miller I can explore the other styles I really love, Jazz and Latin. Because I have these two groups I consciously try to play true to the style, rather than cross pollinating styles. I admire musicians who do that, like David Grisman, but right now I am happy with my approach. Some non-mandolin playing non bluegrass musicians that I admire are; Pedro Padilla, Eliades Ochoa, Art Pepper, John Coltrane, Svend Asmussen, Dirk Powell, Bruce Molsky, David Lindley, Stuff Smith, John Miller, George Barnes, Paulo Moura, The Police, And Nat King Cole (trio).

Q3

Q - How does it feel to own the "world's best Loar F5"? How much work has been done to it since you got it and when did you get it?

Have you found any other mandolins or particular

makers that you feel would be up to par with yours?

Go ahead and get out of the way what type

strings you are using, what type pick, bridge

height at 12th fret and case you travel with?

Do you have any other mandolins and your

thoughts on those?

A - Well I don't know if it is the worlds best mando, but I sure like it. I feel extremely fortunate to own it. There are some others I think are particularly good. David Grisman's 1922 Loar is great. Aubrey Haynie had a fantastic 1925 unsigned F5. I once played the only Loar A5 and thought it was exceptional. There are lots of new mandolins that I think, given time will equal these. I have played many new mandos that I like by makers such as Steve Gilchrist, Mike Kemnitzer, and

Michael Heiden. I got the mandolin in July, 1981. It was in original condition except for a seem separation on the back. I had a radiused fingerboard put on because that is what I was used to, and

the original did not note consistently in tune.

A few years after I got it the top started dipping in under one of the

bridge feet. Todd Phillips thought that if the bottom of the bridge made

consistent contact with the top, it would relieve the pressure in that area. He filled in the bridge bottom between the two feet with ebony and it took care of the problem. Chris Berkov did a little french polish work on the back where the finish started coming off about 1989 or so. I used to brace with my little finger on the top occasionally and eventually wore the finish away. Steve Gilchrist restored it beautifully in 1999. Last year I put Waverlys on it. The originals worked great up until a year or so ago when one of the As started getting sticky. I use D'Addario J75s and a tortoise pick made in the shape of a golden gate. The guy I get them from makes them from old pieces of tortoise he finds in antique and junk stores.

I don't know how high my action is at the twelfth fret, but I would describe it as medium to low action.

I travel with an original Calton case made in England. I own a Heiden F5 with a red spruce top and eastern maple sides. It is a great mandolin with an especially nice high end. I think it is louder than

my Loar. It is still breaking in.

I also own a 1926 F2 and a Lawrence Smart A shaped mandola with f holes. I often string it with the bass strings in octaves. I use it a lot in the studio. With this set up it makes a convincing substitute for a Puerto Rican cuatro or a tres.

Q4

Q - I got a close look at your great Loar a couple of years ago at Kamp

Kaufman. How did you happen to acquire the mando? BTW, no less than Chris Thile told me last fall that he thought your Loar was the best mandolin the world.

It's certainly the best one I've ever heard. What makes it such a great instrument?

A - One of the things I like about my Loar is how balanced it is. I really like the fact that it has a great low end, but the mids and highs are great too.

It has plenty of volume and a nice sustain. Every note has this great

substance to it. The only thing that I would change is having a slightly

wider neck. It is not narrow, but sometimes I think a little more room would be nice.

I got the mando in July, 1981 from a music store in Oakland, Ca. It had been in someone's garage in Walnut Creek, Ca. since the fifties. I think the son of the person who owned it came across it and thought it was worth something. They took it to various music stores and eventually they sold it to Leo's Music. I heard through the grapevine that there was a Loar for sale so I went to check it out. I didn't initially realize how great it was, but it was a Loar, so I decided I would try to get it. I got a loan and sold some instruments( including a 1939 D18!) to raise the money. While I was trying to get the money together, David Grisman made an offer on it. It happened to be one serial number away from the Loar he owned in the sixties and had just reacquired. When he found out I was trying to get it, he didn't pursue

buying it, which I thought was very cool of him. I have a picture of me the day I bought it, exchanging the check for the mando and shaking hands with the salesman.

Q5

Q - Hi John - you were in Red Deer, Alberta with the Jaybirds a while back and I attended a 2 hour mando instruction session with you. You may recall there were 2 lefties in the small group. I was one of them.

I wanted to get your opinion on the use of the pinky finger for chording purposes (notice I didn't use that discriminatory term - left-hand technique). I've heard many on this list espouse the virtue of pinky drills in order to get to a certain level of playing. I vaguely remember you not necessarily agreeing with that view. Can you comment?

A - I probably use my pinky for chording more than I do for soloing. I have been fairly lazy about incorporating my pinky into my single note playing.

I really started working on my little finger when I started trying to play some Jazz tunes in flat keys, in closed positions. When I sit down to practice I use exercises that incorporate all my fingers, including the pinky, but I do not do any specific pinky excursuses. I do recommend using your little finger rather than avoiding it.

Q6

Q - I recently noticed your playing on my son's copy of Raffi's "Let's Play" (gets a lot of airtime in our house). I'm curious how you got involved with Raffi and if you've done other work with him.

A - Raffi lives in Vancouver and records here as well. I do sessions from time to time and his producer, Michael Creber, was familiar with my playing so I got the call. I also played on an earlier Raffi cd called Bananaphone.

Q7

Q - John- I know you play original/jazz/choro tunes with John Miller and

bluegrass with the Jaybirds. In your mind, is there much cross-pollination between the two? Does playing in one group ever give you ideas for the other?

John- what is your mental approach when you play Monroe-style breaks in

the Jaybirds? Your technique and musical thinking seem really different than what I imagine Monroe's was...

A - I don't think there is too much cross polinization between the various

styles I play. I try to play in the style of whichever ensemble I am performing in. Some times I use hammer-on double stops on Jazz tunes I play with J.M., and I think of this as more of a Bluegrass technique, but that is about the only instance I am conscious of.

I like to try and play in a Monroe style from time to time. I find the

syncopated bluesy style breaks a challenge. I have not studied the style to the extent that some players like Mike Compton or Butch Waller. I do, however, try to play in the spirit, if not the exact same notes as Monroe and Frank Wakefield.

My background is more fiddle tune based so, the Monroe style that comes easiest to me is the style that incorporates a steady down up right hand. On the tune Don't Wake Me Up, from the first Jaybirds album,

I drew the inspiration for my solo from Monroe's recording of White House Blues.

I feel that I play the best in the Monroe style when I feel emotionally

charged.

Q8

Q - You have been described as a "tone master" on this list. What do you

consider most critical to obtaining the best tone?

A - I think what is most critical to obtaining good tone is being able to hear good tone.

What one calls good tone is not a universal thing. Someone who loves Bill Monroe's tone might not appreciate Chris Thile's and vice versa. I

appreciate both of their sounds. I really think it is a personal thing and certain types of tone automatically appeal to some people more than others.

You need to decide what sounds right to you.

Q9

Q - I think you are great at writing tunes on the mandolin. I was wondering if you could tell us how you approach writing an instrumental tune on the

mando.

A - I have written tunes in many different ways.

There have been plenty that come from just noodling around on the mando.

Sometimes I will decide on a particular type of tune I want to write, and the key, to get started. You can sometimes end up with something different than you intended.

I started Big Bug as a Monroe style blues in E. I worked on it a long time and it ended up as a breakdown with more notes in the melody.

There have been several that I made up while I was walking, just humming a melody. Some of these are Greenwood, Johnson Warhorse, and Nesser. I think these are some of my strongest melodically speaking. It is interesting finding the right Key and chord changes to these melodies that are not technique based.

I mentioned in an answer to a previous question that sometimes a tune can pop up so quickly that it seems like improvisation. A good example of that is Plum Tree from the new Jaybirds album. I was playing my mando in my back yard on a pretty spring day, and spontaneously composed it in about five minutes. I think it helps to have your mind clear without distractions. I always write when I am alone. It seems the time of day that I am most creative are in the morning or late at night.

Q10

Q - My question regards your tone, considered by many to be the epitome of

tone. What exercises do you recommend for the player who wishes to improve their tone?

A - I have never done any particular exercises for tone.

I have tried to analyze how I get my particular tone.

I think you need to use a pick that will not flex, anything over 1.0 mm. I always use the rounded corners on a standard shaped pick, or a golden gate shape.

I hold the pick pretty firmly, with out clenching it. I think of the pick being locked in my hand. Once the pick is locked, I use the weight of my hand to generate the tone. My right hand makes a fairlywide sweep. I also angle the pick soup a bit so it strikes the string at a slight angle rather than flat against the string.

I usually try to get as little pick noise and as much sustain as possible. When I started out, I think I unconsciously developed the technique it took to create the sort of tone that sounded right to me.

Q11

Q - I think the first time I saw you playing was on the street in Berkeley with Marky Shubb, maybe in the late 70's, give or take a few years. It has been a pleasure watching your career evolve, seeing all the different bands you have played in, and your skills evolve. My question has 2 parts both about improvisation.....first .....when you joined the Tony Rice Unit, I saw that as a major growth step in your playing. Going from a more traditional format of music into a New Acoustic improvising band must have been an exciting and challenging time in your career. What was it like learning so much new material in a short time.........and how did this inspire your playing and improvising skills? And second part, I love your instrumental CD's with what I hear as Monroe or Old Time inspired, but original compositions. I've recently learned one of your tunes, The North Shore, and enjoy the double stops combined in the melody. An incredibly beautiful tune!!! Did you at some time in your evolution delve big time into Big Mon's style? And did you have much personal experience with Bill? Composition, in my mind is just a form of improvising. Do you see it that

way?

A - I believe it must have been 1978 when we first met. You are right about my playing improving during the time I spent with Tony Rice. It was an exciting and challenging opportunity for me, and I felt I had to improve. Tony was great, very supportive of my playing.

I usually learned his new tunes by ear, from tapes he made for me, and from chord charts. I practiced a lot, several hours a day. I practiced not only his tunes but basic technique as well. Tony had very high standards and stressed the three Ts: Timing, Tuning, and Tone. If you had that together, he didn't worry too much about how you soloed. I had learned some Jazz theory before I started playing with T.R., and being in his band gave me a vehicle to apply it.

Having Tony and Todd Phillips playing rhythm behind me automatically made me sound better and inspired me to play in a looser, more creative way. Most of the improvising was modal; the tunes mostly stayed in one key center, so it was not always harmonically challenging. The challenge was having the confidence to go on stage with him. The mandolinists who preceded me on his records were my heroes.

I'm glad you like The North Shore. Those double stops are what I think give the tune its character. I have always loved Monroe's playing. I never studied it exclusively, but enough to try and play in his style on occasion. I admire the way Mike Compton studied Monroe's music so well that he can express himself in that style and sound completely creative.

I was fortunate enough to spend some time around Bill Monroe on several

different occasions. In 1982 The Good Ol' Persons and the Bluegrass Boys

were at the same festival. At some point Bill was playing some tunes for

Paul Shelasky, myself and some others. I was playing his mandolin and he was playing mine! I remember him not being overly friendly, but he was generous enough to spend an hour or so playing requests and answering questions. The G.O.P played Bean Blossom in 1985 and I asked him if he would play Get Up John on stage if I tuned my mandolin to that tuning. He played it great! Another time The G.O.P were playing at Paul's Saloon in S.F. The Bluegrass Boys were playing that same night at another club and finished before we did. We were playing our last set when Bill Monroe, Frank Wakefield , and David Grisman walked in together! After we finished our set, there was a mando jam session with those three, Butch Waller and myself. I feel extremely fortunate to have had these close encounters with such a great musician.

I feel that improvisation is a form of instant composition. I have however, written some tunes so quickly that it seemed like improvisation. Usually it takes more time and thought.

Q12

Q - I'm trying to get beyond the basic "bluegrass chop" into other voicings etc;

1) I've heard you play chords that were almost rock and roll - reminded

me of Chuck Berry. What voicings do you use on that?

2) What type of voicings/substitutions would you suggest as a starting

point for a western swing type back up to such tumes as "Huckleberry

Hornpipe" or similar fiddle tune?

A - I am not sure what chord voicings I use that would suggest Chuck Berry. I do solo using double stops to get a rock and roll sort of sound. Can You give me recorded example of what you are referring to?

I am not an expert on western swing back up. I basically know how to back up fiddle tunes like Sally Goodin. I start with a barred A chord and proceed-

A / A7 / D / Do

A / F#7 / B7 / E7

A / A7 / D / Do

A / B7 / E7 / A

Q13

Q - I have never seen you perform live, but have listened to your recordings

and really admire your tone. Tone is related to your mandolin, technique, etc.

What kind of mic(s) and placement do you prefer in the studio to best

capture your mandolin tone? Any other tips for recording a mandolin are

appreciated.

A - I mostly use a Neumann km 84 or 184. One of the best sounds I have gotten was with a km 54, which I believe is the tube version of a km 84. Other mics have been used on my mando and I find that I like small diaphragm microphones better than large ones, such as a U87.

I usually mic the lower F hole. The mic usually points towards the mando at a slight angle from the right side, approximately 6 to 10 inches away. When I record with John Miller I use two mics in an x/y pattern. The mic capsules are at a right angle to each other with both pointing towards the lower F hole.

Q14

Q - Could you please describe your right hand technique and please provide any tips or insights that you feel are most important to beginning to intermediate players?

A - I lightly rest the base of my palm on the bridge without applying pressure. This places the pick over the fingerboard extension. When I am playing single notes my hand is always in contact with the bridge, sort of gliding over the top of it. I keep my fingers curled into my palm.

I use both a loose, and locked wrist ,depending on the type of tune or

technique I am using. For tremolo and hard driving bluegrass tunes my wrist locks. For fiddle tunes and cross picking my wrist is more loose. My wrist is loosest when I am playing rhythm.

My right hand makes a fairly wide sweep when I am playing aggressively. I move my hand in and out, sort of like a sewing machine to avoid hitting the other strings. Sometimes I compare this motion to a pendulum. For quieter, more melodic tunes this technique is less pronounced.

I think one of the most important things for someone starting out is to use proper pick direction. For most tunes, you need to play the notes that fall on the beat with a down stroke, and the ands with an up stroke. I think the key to this is feeling the timing in your right hand. I almost always keep my right hand subtly moving, falling on the beat just like you would tap your foot. This will help make sure that you will have the right pick direction even during syncopated passages. Having this sorted out will give a fluidity to the rhythm of your notes.

Q15

Q - You play some really varied material. Have you ever tried different

mandolins that were a lot different than the F5 to get a different sound, e.g. bandolim, oval hole, ?? How did you feel about the results? Did some of this make its way to your recordings?

A - I almost always record with my Gibson F5. I do like round sound hole

instruments, though. I bought a 1926 F2 recently and have used it on some old time material in the studio. Playing it takes some getting used to because it responds so differently.

I used a 1923 A4 on some of the cuts on the Jones and Leva cd , Verties

Dream. The first time I played a bandolim I was surprised because most of the Choro players get a bright tone, and I thought it was largely due to the instrument.On the ones I have played, I found you could also get a deep, rich tone as well.

Q16

Q - One of my favorite tunes is "Kenny's Gone" from "The Bumpy Road". Your break on that tune after the intro is fantastic! Can you tell us a little about the tune and Kenny?

A - I like that tune a lot. That John Miller has no shortage of great tunes.

J.M. wrote Kenny's Gone as a tribute to the Jazz musician Kenny Dorham, who he admires. Kenny passed away in the early seventies.

I enjoy playing this tune because, unlike many Jazz tunes, it is in a mando friendly key, F#m, which is the relative minor to A. I find that I don't have to think about the changes so much when I am soloing on it, which is a good thing.