Evan Marshall Discography

Evan Marshall Web site

CoMando Guest of the Week

Children's Mandolin Roundtable

Instruments

A-Style Mandolin

F-Style Mandolin

Mandola and Mandocello

Vintage Dealer's Roundtable

Saturday Morning Luthier's Corner

Mandolin Builder's Super Summit

The Virzi Vortex

Mandolin Buyer's Guide

Music Apps

The Genius of Lloyd Loar

Mandozine Gallery

Vintage Grass Valley Photos

Articles

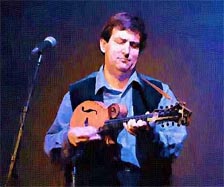

Evan Marshall

Classical music, bluegrass, and pop are fused through the mandolin playing of Evan Marshall. Inspired equally by late classical violinist Jascha Heifitz and the dean of country guitar, Chet Atkins, Marshall has crafted a highly experimental approach to the mandolin that blends bass lines, chordal accompaniment, and tremolo melodies without overdubs.

Classical music, bluegrass, and pop are fused through the mandolin playing of Evan Marshall. Inspired equally by late classical violinist Jascha Heifitz and the dean of country guitar, Chet Atkins, Marshall has crafted a highly experimental approach to the mandolin that blends bass lines, chordal accompaniment, and tremolo melodies without overdubs.

Although he studied classical violin as a youngster, which remained my main instrument until age 22, Marshall found his natural musical voice on the mandolin at the age of 14. Marshall stepped forward as a composer on his first solo album, Mandolin Unlimited, released as an LP and cassette by Rounder in 1987. Produced by Mark O'Connor, the album includes solo tracks with overdubbed double mandolin pieces and several tunes featuring Sam Bush and Mark O'Connor on mandolin and John Knowles on guitar. Marshall's 1990 album, Mandolin Magic, was produced by David Grisman and featured solo mandolin interpretations of songs by the Beatles ("Do You Want to Know a Secret," "Mother Nature's Son," "Michelle," and "You Won't See Me"), Gershwin ("Summertime"), Johannes Brahms ("Hungarian Dances #5 and #6"), Jacques Offenbach ("Bacarolle"), and Don McLean ("Vincent"). Marshall continued to showcase his interpretive skills on his second album, Evan Marshall Is the Lone Arranger, released in 1995. In addition to two more Beatles tunes ("P.S. I Love You" and "Here, There and Everywhere"), Marshall reworks Gershwin's "Someone to Watch Over Me", Berlin's "Dancing Cheek to Cheek", and Rossini's "William Tell Overture."

Q1

Q - I hadn't heard anyone do duo style besides yourself and a few classical players until recently. A friend sent me a video DVD of a Brazilian club date by Hamilton de Holanda and his band, and HH does some great duo style on his 10 string bandolim. Are you familiar with some of the Brazilian bandolim players and their music?

A - Thanks for helping. I'm sorry to say that this is the first time I've

heard of Hamilton de Holanda. My knowledge of the Brazilian bandolim

heritage is very limited. I've heard some of the Jacob do Bandolim tracks

reissued by Acoustic Disc, and that's about it so far. Sorry. :-)

Q2

Q - How in the hell did you learn to do that duo style? That just seems impossible to me.

A - About a year and a half out of college, I decided to change my emphasis

from violin to mandolin. (The allmusic bio blurs this, I think; I started

playing mandolin at age 14, but my main instrument continued to be violin

until age 22.) I decided that I needed to figure out a way to be employable

on a steady gig/job as a mandolinist without having to depend on other

players being available or willing, so I had to become a solo performer.

Also, a soloist would cost a prospective employer less than an ensemble or

band. The year was 1982, and my attempts to research prior solo mandolin

performance yielded nothing. I had been familiar with John Williams' (the

guitarist) recording of Recuerdos de la Alhambra for quite some time, and I

thought, "If a solo guitarist can sound like he's playing a duet, perhaps a

solo mandolinist can also." I worked on Recuerdos (from the sheet music) for

about three months before the first time I tried to play it publicly, but my

own duo-style arranging process really started to come together quickly

after that. Starting with Recuerdos probably steered me in the direction of

a somewhat different approach to duo-style from Francia and Pettine, who I

hadn't heard of yet. More about this last point in further postings.

Comments from Lumpy:

I'd like to comment just a bit on the experiences I had with my old friend, Evan Marshall, when he was just starting the mandolin.

Evan, and I went to high school together. He showed up one day at the talent show audition with his violin and his older brother, John, also a violinist.

This led to that and we ended up forming a little bluegrass combo, "Smokewood". Initially, one guitar, one banjo and two fiddles, we handed Evan a roundback

mando that belonged to our banjo player's dad and said "here kid, it's tuned like your violin". Evan still has that roundback, hanging on his wall in San Gabriel.

It was only a couple days till Evan was doing some pretty remarkable things. I know Evan says "Recuerdos" was his first duo style arrangement, but I recall it

happening much earlier. Evan used to do a duo style arrangement of "Orange Blossom Special" on mando that the crowds always loved. He then applied his arranging

skills to that tune and created "Orange Blossom Derigible", "Frailing My Face with his Fingers" and several others.

Evan was always a master arranger, even as a 14 year old. He was generally the one responsible for the successful arrangements that out old band did back then. And without his playing in the mix, we would have been just another couple guys playing "Foggy Mtn Breakdown".

Thanks for the memories, E-Van..:-)

Lumpy

A - Thanks for the kind words, Craig, er, I mean Lumpy. :-) Keep pickin' that

great fingerstyle guitar.

Q3

Q - I absolutely love your version of the "William Tell Overture." I am

thinking of transcribing it (or trying to anyway) for study purposes, would you

be willing to check my results for me once I'm done?

A - I hope to publish my arrangement in printed form in the not too distant

future. I'll try to help on an individual basis as time allows... :-)

Q4

Q - I was in the audience when you played in Walnut Creek, CA., must be a coupla years ago now. As I recall you were playing a Gilchrist Model F5C, his classical mandolin. Can you tell up a bit about the instrument and your impressions of it? By the way, it was a very enjoyable solo performance. I was the guy with my mouth wide open in amazement. you indeed use every available note, in fact I think you played every note, some simultaneously, how did you develop your duo style? Any new recording projects in the works? How about plans to play again in the SF Bay Area?

A - My Gilchrist Model 5C is absolutely the most Evan-friendly instrument I've

ever had my hands on. I'm thrilled with the sound we get as a team. I

haven't made a solo recording with it yet; the quartet pieces on "The

Bridges of Orange County", i.e., Vanilla Schubert and The Lark, are the only

tracks with my Gilchrist so far (available via bridgesoforangecounty.com).

The main adjustment I had to make when switching from my Gibson F5-L was

learning not to let the lighter (re weight) Gilchrist move in phase with my

picking arm.

My first attempt to play in duo-style was learning Recuerdos de la

Alhambra. (Kind of like learning "The Raven" as one's first attempt to

memorize poetry.) After learning Recuerdos, I figured out playing moves a la

Recuerdos with different "denominators", such as one bass note plus five

tremolo notes, one bass note plus seven tremolo notes, one bass note plus

nine tremolo notes, one bass note plus an indefinite number of tremolo

notes, and then adding chord plus melody moves to the above. There's

definitely a learning curve; I really don't think about the math that much

while I'm playing now.

Q5

Q - You are a master of the duo style of mandolin playing. Marilyn Mair tried explaining how to do it, but she kind of glossed over the whole subject (I even have an old article where Dawg Grisman tried to explain it, but he was too brief as well. There has to be more to it than just getting a tremolo going and adding a couple notes on the side). Could you go into detail -- maybe several posts -- as to how the magic is made? Also any recommendations on method books covering this would be appreciated. I've heard the Pettini method mentioned a couple of times.

By the way, I have two of your very excellent CDs. Is a third on the way yet?

A - Thanks for your kind words. Imagine playing a fast yet smooth tremolo on

your open A string(s). Without slowing down or roughing up your tremolo, one

of your downstrokes picks your open D string(s) and skips past the A

string(s). You then resume tremoloing the A string(s) on the very next

upstroke. The A note should sound as if it were never interrupted, because

it was still ringing when it wasn't articulated for that one pickstroke.

This is the general essence of duo-style; a tremolo melody on a higher

string sounds uninterrupted by single-stroke accompaniment notes on a lower

string. (The tremolo melody is rarely on a lower string than the

single-stroke accompaniment notes.)

I am currently working on a duo-style method book that I will recommend

wholeheartedly upon completion. :-) The first part of this book-in-progess

appeared in two recent issues of Mandolin Quarterly. These MQ excerpts will

definitely get you started.

Three more solo CDs are in the works. I have a chamber music CD, "The

Bridges of Orange County", available via emandolin.com or

bridgesoforangecounty.com, and a band CD, "Billy and the Hillbillies" (with

my band that performs regularly at Disneyland), available via

billyandthehillbillies.com.

Q6

Q - Any new recording projects in the works? How about plans to play again in the SF Bay Area?

A - I'm hoping to record a classical solo CD and a Christmas solo CD in the near

future. I have several book projects under way, including sheet music

editions of these CD programs (playable as very advanced solos or

intermediate to advanced level duets), and several method books, including

duo-style from entry level to advanced.

I don't think I have anything on the books for the SF Bay Area at present.

I'll be performing and giving a workshop at the Port Orford, OR Arts

Festival 8/30 & 8/31, soloing with Orchestra Seattle 9/7 (tentative), and

performing three times daily with Billy and the Hillbillies at the Western

Washington Fair in Puyallup, WA, 9/5 - 9/21. When at home in Los Angeles, I

continue to play 5 shows a day, 5 days a week at Disneyland.

Q7

Q - What sort of playlist do you have with the band at Disneyland? How did you

develop it? And, how did you come to get the job there?

A - Billy and the Hillbillies' premise is hot pickin' with a lot of comic shtick

and funny vocals, like a 2nd or 3rd generation version of Homer and Jethro.

Our current show, which will change somewhat in October, always includes

"Billy Tell" (my solo mandolin version of the finale of the Wm. Tell

Overture), "Orange Blossom Special" with forays into "Zorba the Greek" and

"Holiday for Strings", a medley of "Under the Double Eagle" and "It's a

Small World", and "Puddle Prance", our tribute(???) to Riverdance. We also

rotate in "Thunder Mountain Dew", a couple of Elvis medleys, Bluegrass

standards like "Rocky Top" and "Ol' Slewfoot", and Oldies, such as "Stayin'

Alive", which is an example of Country-Disco, or "Crisco". We have performed

about 10,500 shows in Disneyland's Golden Horseshoe theater since December

1992; our show was originally our best material from our "street"

performances on the Fair circuit and in Disneyland's Frontierland and

Critter Country. The band consists of myself, my brother John, Kirk Wall,

and Dennis Fetchet, as well as some substitutes who drop in from time to

time. Our "foot in the door" came in May 1988, when John, Kirk, & Dennis

answered a Disneyland casting call and auditioned successfully for the "Pig

Race Band", also known as "The Barley Boys". Sounds like a glamorous

beginning, doesn't it?

Q8

A - This was not specifically addressed to me, but I'd love to weigh in - - :-)

Should you keep your right hand free-floating? Should you drag your pinkie

fingernail along the finger-rest/pickguard? Is it okay to plant pinkie (and

ring-finger ?!?!?)? Should your right wrist be your main hinge? Your forearm

rotators? Your right elbow??? During the course of any given day, my right

hand and arm answer yes to all of the above questions, at least for a

moment. I have two guiding principles:

1. Whatever can/may be relaxed, should be relaxed. Put another way: Avoid

any unnecessary muscle tension. Any physical task, including playing the mandolin, requires a certain level of muscle tension; the less you exceed the minimum of muscle

tension necessary to accomplish the desired task, the more likely you are to

avoid overuse and misuse injuries, injuries which cause an undesirable

reduction in worldwide mandolin activity.

2. Allow yourself to have more than one way of addressing the mandolin with

your right hand, if that is what the artist within requires for maximum

expression. Just remember to practice those passages where you change mode

of right hand address with a little extra diligence. And always remember

principle #1.

Q9

Q - First, I'm assuming such a demanding technique would require that you

practice quite a bit... how much practice time do you put in and what

specifically do you practice?

Also, are you able to improvise using your style, and if so, how and

where do you get to do that?

A - I've always been very devoted to daily practicing. I would say that I have

my hands on the mandolin for three to five hours over an eight-hour to

ten-hour span, most days. My ideal practice day, toward which I strive every

day and sometimes come close, is 20 or 25 minutes of scale studies in the

"key of the day" (rotating through all 24 major and minor keys every month

or two, per the advice of the great violin teacher Carl Flesch), and

dividing the rest of the time between running pieces and taking pieces

apart, phrase by phrase, bar by bar, beat by beat. I hope to publish my

original scale studies (and much more) in the near future. I could go into

detail about the scale studies if anyone would like.

I don't improvise in duo-style in concert, except perhaps to try to hide a

mistake from the audience. I used to improvise in duo-style when I strolled

tables in restaurants; I might improvise in duo-style at a wedding ceremony

if we need an extra half-minute between the flower girls and the entrance of

the bride. :-)

Q10

Q - Evan, at some point every CGOW has to tell us about all of his instruments. You might as well get it over with. What's in your herd?

A - I own a 1981 Gibson F5-L which was my main instrument from 1981 to 1999;

it's the instrument I played on Mandolin Unlimited, Mandolin Magic, and Lone

Arranger. I also own two custom 8-string electrics by John Di Trapani; one

is like a miniature Les Paul copy, while the other is like a miniature

Howard Roberts model. I used the Les Paul-style mando to great effect as a

rock-grass ax in the 1980s. I own a 100-year-old Rex bowl-back (Lumpy

mentioned it) which I need to mend a little so I can use it as a baroque

mandolin. But my full-time partner without exception since November 1999 has

been my Gilchrist 5C. Steve built it to sound great with light-gauge

strings; I can barely put it down.

Q11

Q - "answered a Disneyland casting call and auditioned successfully for the "Pig Race Band", also known as "The Barley Boys". Sounds like a glamorous beginning, doesn't it?"

Hey, don't knock pig races. The best paying continuous gig I ever had

was calling pig races at a big u-pick punkin patch. I wore bib overalls and

a straw hat and sat on the porch playing clawhammer banjo between races.

If you wanna' be a star you got to pay some dues.

Wonder how much I still owe?

A - I didn't mean to knock pig races or any other gig. :-) Some of the best

growth as a player can come from the least glamorous gigs. I developed four

hours of A+ to B+ solo mandolin repertory strolling tables at restaurants

over a 10-year stretch. Buddy Holly and Sonny Curtis developed the Crickets'

signature "rhythm leads" on guitar (in which the player does the same

rhythmic figure on several different dispositions of the same chord) playing

at a roller rink, trying to hear acoustic guitars above the noise.

Besides, where else but pig races can you root for Miss Piggy to beat Sir

Francis Bacon?

Q12

Q - I hear rumors that you're playing unamplified now. Is that true? If so, why? And, if so, are you using any heavier strings than you used to?

Are you still performing concerts as a soloist, or did your experiments w/ accompanists a few years ago lead to any steady duo or trios?

A - Rumors that I'm playing unamplified...Hmmm...I've always considered myself

an acoustic mandolinist who believes in sound reinforcement rather than an

electric mandolinist...One thing that is different: my 1999 Gilchrist 5C was

custom-built to live with light-gauge strings; if I perform acoustically

with a classical guitarist, I don't need to fear an unfavorable comparison

re tone or volume. I've been a Guest Artist on about 30 Symphony Pops dates

in the last four years; I still send both a processed pickup and mic signal

to the audio engineer's board to compete with a full brass section. I also

send both a pickup and mic signal to the audio engineer's board at

Disneyland; the Golden Horseshoe is much closer to vaudeville than the

concert hall (a mandolinist has to make a living...). But really, I'm an

acoustic mandolinist... :-)

I had a quartet that was active from 1997 until 2001, the Bridges of

Orange County. We made a CD, which is still available through our website,

bridgesoforangecounty.com, but that group is no longer playing together. I

would love to play more chamber music; finding the personnel, time, and

opportunities has been a challenge. On the other hand, I am more

enthusiastic and optimistic about solo mandolin performance than I have been

in years. I am seeking solo engagements more vigorously, I am preparing two

solo CD programs for recording, and I have begun work on two repertory books

and six method books (now, if I could just finish one...).

Q13

Q - Evan, who are some of your favorite mandolin players who you like to

listen to? Favorite other musicians?

A - A list of my favorite mandolinists makes me a little nervous; there are

about 25 that come to mind, but I'm afraid I'll leave somebody's name off.

The two I've listened to the most on the living room stereo over the years

are Don Stiernberg and Ugo Orlandi. Marty Stuart left me speechless when I

heard his solos on Lester Flatt Live! in 1974. Chris Thiele's performances

of his own Caprice #1 and Bach's Solo Violin Sonata #1 (BWV 1001) at CMSA

2000 inspired me to work on my own solo performance career with renewed

zeal.

My four biggest heroes who were never mandolinists: Violinists Jascha

Heifetz and Itzhak Perlman, and Country Guitarists Chet Atkins and Jerry

Reed. I think pre-movie-star Jerry Reed had the greatest combination of

stage persona, virtuosity, and musicality that a picker could ever hope to

have.

Q14

Q - Could you please give us a sneak preview of your concerts and / or clinics that you will be offering at the CMSA convention in October?

A - In concert/recital I will present two forty-five minute sets of solo

mandolin repertory. (It is yet to be decided whether these will comprise one

full-length program or be part of two separate programs on two separate

evenings.) The programs will include my Five Caprices (recently revised

extensively), Vanilla Schubert (recently revised extensively), the William

Tell Overture (all four major sections, not just the finale/"Lone Ranger"

section), Joyful Variations on a Theme of Beethoven (a recent duo-style

composition/arrangement of mine), Hungarian Dances #5, 6, & 7 by Brahms, a

duo-style version of the Pastorale from Handel's Messiah, and a few other

short pieces. I hope also to perform several pieces with my sudent, Scott

Gates, at one of the Wine & Cheese concerts.

I believe I'm tentatively scheduled to give two seminars; one will focus

on developing right-hand technique (including duo-style), and the other will

focus on developing left-hand technique.

Q15

Q - I really enjoy your chamber music CD and would like to hear you create

more music in that format. You must be a good actor or have multiple personalities to go from a Disney mando playing character to more serious musical endeavors. Do you enjoy the schtick? I could see it being fun and I'm sure that a regular gig like that allows you to earn a living so you can create what is possibly less commercial music...... but art that is more personal to you. How do you find balance in both?

One more question on your Gilchrist Classical F5C, what kind of strings

are you running on it? And what kind of pick do you prefer?

A - I would love to spend more time on chamber music; I hope to play and record more chamber music in the future.

To be honest, you've hit the nail on the head. I hope someday to make my

living giving concerts, publishing study materials, sheet music, and

recordings, and teaching; until that time, being a full-time hillbilly at

Disneyland works pretty well. A few things help with the balance you

mentioned:

1. Besides duo-style and Italian-school classical, my other great

mando-loves are pickin' bluegrass, country, and swing. Since showmanship and

shtick are part of the job description at Disneyland, it gives me a chance

to emulate two of my heroes, Jerry Reed and Jethro Burns.

2. I am almost manic about using my break time between shows to practice

my art repertory.

3. I'm almost shameless about incorporating difficult passages from my art

repertory into the Disneyland show. As an example, one of my classical

"superlicks" is a rapid, descending two-octave chromatic scale in multiple

pull-offs followed by an ascending three-octave arpeggio lick. This lick

occurs in my cadenza for the Hummel Concerto Rondo, track #5 on "The Bridges

of Orange County" (

I use extra light strings, either D'Addario or Ernie Ball, and I round the

edges on a medium-thin Clayton USA pick with an emery board. I imagine some

of you are raising your eyebrows pretty high now. Before you jump to any

conclusions, please a) remember Larry saying how well Bjorn Borg's racquet

worked for Bjorn Borg, and b) listen to the mandolin work on "Lone

Arranger", "Mandolin Magic", "The Bridges of Orange County", and/or the

"Billy and the Hillbillies" CD (

Q16

Q - I was at DLand in May...and happened on the Golden Horseshoe Salon. Anyway, someone said that there was a bluegrass band gonna play so I stayed. I almost fell outa my chair laughing and was just amazed at Evans rendition of Wm Tell. And the speed record thing for Orange Blossom Special was cool.

1. How does he stay "up" doing the same show for so long. Do they vary it.

2. What mando does he play.

3. What is his practice routine.

A - I'm glad to hear how much you liked the show. The main things that

help me stay "up" doing the same show for so long:

1) Reminding myself that I get to play "Billy Tell" for 5,000 or 6,000

people a week without going on the road;

2) Connecting with new audience members every show; and

3) Reminding myself that I have lots of break time between shows to

practice my art repertory. :-)

We vary the show a little, rotating a couple dozen songs into the first

half, but the second half's song list never changes.

I play a custom-built Gilchrist 5C with extra light strings.

Re practice (from an earlier response):

I've always been very devoted to daily practicing. I would say that I have

my hands on the mandolin for three to five hours over an eight-hour to

ten-hour span, most days. My ideal practice day, toward which I strive every

day and sometimes come close, is 20 or 25 minutes of scale studies in the

"key of the day" (rotating through all 24 major and minor keys every month

or two, per the advice of the great violin teacher Carl Flesch), and

dividing the rest of the time between running pieces and taking pieces

apart, phrase by phrase, bar by bar, beat by beat. I hope to publish my

original scale studies (and much more) in the near future. I could go into

detail about the scale studies if anyone would like.

Q17

From Evan: "I hope to publish my original scale studies (and much more) in the near future. I could go into detail about the scale studies if anyone would like."

A - The scale studies I try to do every day:

1) Measured "Keyboard" Trills - - Measured trills at a moderate tempo,

with the added challenge that keyboardists face (hence the name): Lift up

the lower finger when you put the higher finger down (normally a string

player would leave first finger down during the entirety of a trill from

first to second finger). After one has done these for a few months, one

might try Anchored Measured "Keyboard" Trills, e.g., fretting the D

string(s) silently with first and fourth fingers while playing a Measured

"Keyboard" Trill on the G string(s) with second and third fingers.

2) Finger-Pedaling Exercises - - The idea behind Finger-Pedaling Exercises

could be illustrated like this:

3 2 4 3 4 2 3 1 4 3 4 1

1 1 2 2

The lower line indicates finger numbers on the G string(s); the higher

line indicates finger numbers on the D string(s). Every note on the G

string(s) is sustained under the changing D string notes until the next G

string note is articulated. You are accomplishing a task akin to a piano's

sustain pedal, only you are doing it with uninterrupted fretting.

3) Three-Octave Scale (very similar to the ones in Chris Thile's video),

ascending and descending.

4) Three-Octave Arpeggios beginning and ending on root, third, and fifth,

ascending and descending.

5) Broken Thirds (zig-zag scales: a-c-b-d c-e-d-f e-g-f-a, etc.) through

two octaves, no shifts of position, ascending and descending.

6) Broken Thirds (zig-zag scales: a-c-b-d c-e-d-f e-g-f-a, etc.) through

a tenth, E string(s) only, three shifts of position, ascending and

descending.

I try to cycle through all 24 major and minor keys every six weeks or so.

These are very taxing on your fingers, especially at first, especially #1

& #2. NEVER IGNORE PAIN!!! Rest your fingers often, consider using a lighter

gauge set of strings, go slowly and gradually, have fun, and NEVER IGNORE

PAIN!!!

Q18

Q - As an athlete, I am curious about physical fitness, as I'm sure it is one

thing that many don't equate with being a musician. With your emphasis on

"never ignore pain" and in regards to your rigorous playing schedule, do

you have any type of physical training program? Hand stretches or the like?

How about back and legs, seeing how you spend a lot of time on stage?

A - I'm sure I don't think about physical fitness as much as I

should; the show at Disneyland is somewhat aerobic, as we do a fair amount

of dancing (not necessarily good dancing) and moving around. I could do

more, though. My brother, on the other hand, slaps the tar out of a bass

fiddle for five shows a day, and swims a mile once or twice a day, five or

six days a week.

There's no question that physical fitness is very good for the longevity

of a musician's career. A few years ago Keith Harris translated a book by a

German musician and kinesiologist. If you go to mandolincafe.com, click on

Plucked String, Inc., and search "books", you'll find this listing:

Author: Exercises for Musicians: How to Combat Effects of Postural Stress

Item: by Ekard Lind. Trans. Keith Harris

Item Number: Paperback

Price: $10.00

Instrument: Book

I suppose the listing is a little mixed up, but I've heard good things

about the book. :-)

Regarding taking care of the hands and fingers, I have some definite

ideas:

- - I like to put my hands in very warm water for a minute before playing

when I have the opportunity.

- - Build up to playing longer and harder gradually.

- - Play in front of a mirror occasionally and try to spot examples of

unnecessary muscle tension in your playing.

- - Don't keep doing something that hurts; give it a rest. I have had to

set aside the mandolin.for a week at a time because I practiced multiple

pull-offs too long without interruption, ignoring signals from my body that

it was time to work on something else.

- - Use a raised adrenaline level to your advantage. Logging

moderate-pressure performance time, like giving a living room concert for

family and friends, or jamming/playing chamber music with people you hardly

know, will bring you face to face with mild "stagefright". Experiencing a

little stagefright on a regular basis will help you reach new plateaus

faster regarding complexity of music on which you can concentrate

successfully, development of your ear-to-hand coordination, and training of

the muscles and tendons most directly involved in playing the mandolin.

Q19

Q - With such a heavy practice schedule--can you recommend some warm up

techniques that will prevent injury from over use (tendonitis, etc), books,

or any other suggestions? Have you ever dealt with this?

I believe that the legions of "baby boomers" taking up mando these days have

to seriously consider this if they want a long and active mando playing life

in the years to come!!

A - I'll start by quoting another response I just wrote:

"Regarding taking care of the hands and fingers, I have some definite

ideas:

" - - I like to put my hands in very warm water for a minute before

playing when I have the opportunity.

" - - Build up to playing longer and harder gradually.

" - - Play in front of a mirror occasionally and try to spot examples of

unnecessary muscle tension in your playing.

" - - Don't keep doing something that hurts; give it a rest. I have had to

set aside the mandolin.for a week at a time because I practiced multiple

pull-offs too long without interruption, ignoring signals from my body that

it was time to work on something else.

" - - Use a raised adrenaline level to your advantage. Logging

moderate-pressure performance time, like giving a living room concert for

family and friends, or jamming/playing chamber music with people you hardly

know, will bring you face to face with mild "stagefright". Experiencing a

little stagefright on a regular basis will help you reach new plateaus

faster regarding complexity of music on which you can concentrate

successfully, development of your ear-to-hand coordination, and training of

the muscles and tendons most directly involved in playing the mandolin."

Specifically regarding warming up, I'm fond of warming up my hands with

very warm water, as noted above. Play slowly and easily at first, easing

into playing hard and intensely. It is also good to have a favorite warm-up

study piece, one that you would never play for an audience, for

psychological reasons as much as physical. Mine is Kreutzer's Study Piece #

9 for violin. Since I would never play this piece for an audience, I allow

myself to play it slowly and easily at first; it's hard to "reign in the

racehorses" on hot licks that give you great joy when played at full

intensity, and trying to play them at full intensity before you're ready can

lead to pain and frustration. This is especially important when you're about

to go on stage in a high-pressure situation. Blowing your hottest lick in

the wings just before you go on can hurt your confidence. If I stumble on

Kreutzer # 9 in the wings, I tend to let it go pretty easily. Kreutzer # 9

is a rather difficult study piece; you may want to work up to it gradually.

:-)

I have had a tendinitis problem in my left pinkie that started 20 years

ago when it got caught in a slamming car door (1973 Lincoln Continental),

but my left pinkie is now in the best shape it's been in since before the

accident; I work it very hard, but I also rest it frequently, and I try to

use alternate fingerings if the phrasing allows.

Q20

Q - I'm a novice and sort of figuring this mandolin thing out in a vacuum. so I

apologize if this has been discussed many times before, but...when

you play four finger chords where should your thumb be placed?

wrapped around the neck or behind the neck?

A - I put my thumb about halfway between the two extremes Sam mentions: The

inside tip of my thumb usually rests against the neck at a point about

halfway between the fretboard and the neck's midline. But I also sometimes

put the end of my thumb directly behind the neck's midline, especially for

big stretches like the diminished 7th chord voiced as three consecutive

major 6ths. I allow myself to have more than one way that my left hand

addresses the mandolin (I also allow myself to have more than one way that

my right hand addresses the mandolin); the important cosideration is to

remember to practice those passages that contain a change of address, so to

speak, with extra diligence, so that negotiating those changes of address

becomes second nature.

Emanuil Sheynkman talked about putting the neck of the mandolin in the "V"

of your left hand so that there was a window between the neck's midline and

the vertex of the V just big enough to push a pencil through. :-)

Q21

Q - I really enjoy your two solo albums. I am primarily a

classical guitarist who plays a little mandolin as a

change of pace, your albums really opened my eyes

up to what could be done with a pick.

Recently, Marilynn Mair briefly mentioned classical

duo style mandolin in this forum. How does your

duo approach differ, if at all from the traditional

classical style? Are there any elements of the classical

duo style that you later brought into your own playing?

A - I'd like to start by quoting an earlier response of mine:

"Duo-style combines a tremolo voice (usually higher) with single-attack

accompaniment notes (usually lower). Classical guitar has a kissing cousin

to duo-style, called 'tremolo study'. In tremolo studies, every beat is

often a four-note figure; the four notes of the figure are delegated

bass-tremolo-tremolo-tremolo. For example, if the music contained a passage

of repeated A bass notes under a long high E, it would be written A-E-E-E

A-E-E-E A-E-E-E, etc. The right-hand fingering would be

thumb-ring-middle-index thumb-ring-middle-index thumb-ring-middle-index,

or p-a-m-i p-a-m-i p-a-m-i. I decided to play these figures on mandolin

as down-up-down-up down-up-down-up down-up-down-up, all alternate

picking. After learning Recuerdos, I figured out playing moves a la

Recuerdos with different 'denominators', such as one bass note plus five

tremolo notes per beat, one bass note plus seven tremolo notes, one bass

note plus nine tremolo notes, one bass note plus an indefinite number of

tremolo notes, and then adding chord plus melody moves to the above.

"Not everyone who has tried this on mandolin has had the same approach.

One hundred years ago Leopoldo Francia told his students to play these

4-note figures down-down-up-down down-down-up-down, starting every beat

with a down-stroke glide. An acquaintance of mine told me she was taught to

start every beat with a down-stroke glide and never to worry about how many

pick-strokes she played per beat. Pettine may have played double-stops

(e.g., the A & E together) on the downbeats ( AE-E-E-E AE-E-E-E AE-E-E-E )

as the rule rather than the exception. Even after learning about these other

approaches, I have retained A-E-E-E A-E-E-E A-E-E-E played

down-up-down-up down-up-down-up down-up-down-up as my 'default' setting;

playing double-stops on the downbeats only occasionally helps the two voices

to sound phrased differently, creating the sound of a true duet played by

one person."

How does my duo-style approach differ from the traditional classical

style? It depends whom you ask. I met Ugo Orlandi at CMSA in MT 10/2001; he

told me that he agreed with me, i.e., that A-E-E-E A-E-E-E A-E-E-E played

down-up-down-up down-up-down-up down-up-down-up (or any other

bass-tremolo-tremolo-tremolo/low-high-high-high figure played

down-up-down-up with the two "voices" on two different pairs of strings) as

one's 'default' setting is what he defines as duo-style. Starting every beat

with a down-stroke glide, as Leopoldo Francia apparently played/taught,

would be classified by Ugo as "arpeggio", similar to the sense in which

"arpeggio" instructs a violinist to play 3 or 4 different chord tones one

after the other on 3 or 4 different strings with a single down-bow (or

up-bow). The one thing virtually everyone seems to agree on is that

duo-style is a tremolo voice and a single note voice sounding at the same

time on one mandolin. :-)

Q22

Q - Since you are one of the prime contemporary players of the duo style how did you come across this playing technique? Did you first hear the old masters like Calace and Pettine or did you discover the technique on your own?

A - I discovered the technique on my own, and I thought I had invented

something nifty. A year or so after I started seriously developing my "new"

technique, I found out it already had a name, and a heritage with some

variety of approach. Quoting myself from earlier this week:

"I decided that I needed to figure out a way to be employable on a steady

gig/job as a mandolinist without having to depend on other players being

available or willing, so I had to become a solo performer. Also, a soloist

would cost a prospective employer less than an ensemble or band. The year

was 1982, and my attempts to research prior solo mandolin performance

yielded nothing. I had been familiar with John Williams' (the guitarist)

recording of Recuerdos de la Alhambra for quite some time, and I thought,

'If a solo guitarist can sound like he's playing a duet, perhaps a solo

mandolinist can also.' I worked on Recuerdos (from the sheet music) for

about three months before the first time I tried to play it publicly, but my

own duo-style arranging process really started to come together quickly

after that."

Duo-style combines a tremolo voice (usually higher) with single-attack

accompaniment notes (usually lower). Classical guitar has a kissing cousin

to duo-style, called "tremolo study". In tremolo studies, every beat is

often a four-note figure; the four notes of the figure are delegated

bass-tremolo-tremolo-tremolo. For example, if the music contained a passage

of repeated A bass notes under a long high E, it would be written A-E-E-E

A-E-E-E A-E-E-E, etc. The right-hand fingering would be

thumb-ring-middle-index thumb-ring-middle-index thumb-ring-middle-index,

or p-a-m-i p-a-m-i p-a-m-i. I decided to play these figures on mandolin

as down-up-down-up down-up-down-up down-up-down-up, all alternate

picking. After learning Recuerdos, I figured out playing moves a la

Recuerdos with different "denominators", such as one bass note plus five

tremolo notes per beat, one bass note plus seven tremolo notes, one bass

note plus nine tremolo notes, one bass note plus an indefinite number of

tremolo notes, and then adding chord plus melody moves to the above.

Not everyone who has tried this on mandolin has had the same approach. One

hundred years ago Leopoldo Francia told his students to play these 4-note

figures down-down-up-down down-down-up-down, starting every beat with a

down-stroke glide. An acquaintance of mine told me she was taught to start

every beat with a down-stroke glide and never to worry about how many

pick-strokes she played per beat. Pettine may have played double-stops

(e.g., the A & E together) on the downbeats ( AE-E-E-E AE-E-E-E AE-E-E-E )

as the rule rather than the exception. Even after learning about these other

approaches, I have retained A-E-E-E A-E-E-E A-E-E-E played

down-up-down-up down-up-down-up down-up-down-up as my "default" setting;

playing double-stops on the downbeats only occasionally helps the two voices

to sound phrased differently, creating the sound of a true duet played by

one person.

Q22

I'd like to jump into the "Broken Record" and "Art of Practicing" threads because Practice Strategies and Methods are favorite topics of mine, and also because I was mentioned and paraphrased a couple of times.

I understand from my dictionary that "rehearse" comes from the Old French "rehercer", literally, to harrow (phase 2 of preparing a field for planting after plowing) again. What a great word picture: Repetition of the process of making the soil ready for fruitful planting. Harvesting is still months down the road! Perhaps rehearsing/practicing is an investment of time with a long-term return...

Marilynn pointed out the difference we English-speakers make between practicing individually and rehearsing as a group (practice your individual part before you rehearse), but certainly there is a common historical perspective: Both processes require attention to detail and repetition. Running an entire piece over and over may be repetition, but not repetition combined with attention to detail. To those of you who recently have become "broken records" during your individual practice time, congratulations on your discovery! If I may suggest, remember three things:

1) Make sure your progressive segments overlap! For instance, when practicing repeatable segments of two measures, i.e., working on measures 1-2, mm. 3-4, mm. 5-6, etc., don't forget to practice mm. 2-3, mm. 4-5, etc., so that there are no transitions left unpracticed.

2) Address and fix the problems your "microscope" reveals.

3) Press the "Refresh" button on your brain; if mm. 3-4 need a lot of work, alternate "normal" repetitions with quiet or loud or picked-near-the-bridge repetitions (Good call, Richard Bailey!).

A friendly word of caution to Mark ("Snowball-method") and Larry ("Reverse-snowball-method"): If you have practiced measure #1 100 times as often as measure #100 (or vice versa), and measure #1 is the same level of difficulty as measure #100, you may

have been inefficient with precious practice time. I hope I sound like I'm disagreeing agreeably. :-)

Richard B. writes further, "I have a book called 'The Art of Practicing', and the author puts forth the idea that practice shouldn't be just scales and exercises, but wide open playing with all the fun of actually playing a musical phrase." Carl Flesch suggested a three-way division of practice time: Scales and exercises, attention to details of actual pieces of repertory, and running entire pieces. Without those scales or patterns-for-Jazz-improvisation or something like these in all 24 keys, you may limit yourself to truly opening up in only two or three keys. :-)

Viva la discussion!

Evan Marshall

Q23

"To Think Or Not To Think" is a long-standing debate in the creation and performance of music, relating to both improvised forms and completely notated repertory. In his Foreward to Jerry Coker's landmark book,"Improvising Jazz", Gunther Schuller refers to the idea that great improvised solos do not involve some type of thinking as a deception: "This deception was and is possible because very few people make the distinction between what is conscious and what is subconscious in the creative process...'Inspiration' occurs precisely at that moment when the most complete mental and psychological preparation for a given task (be it only the choice of the next note, for example) has been achieved [p. ix]." Prof. Coker then lists the improviser's "five basic tools" on page 3: "intuition, intellect, emotion, sense of pitch, and habit." Since "four of these elements (intuition, emotion, sense of pitch, and habit) are largely subconscious...any control over improvisation must originate

in the intellect."

The crux of the matter seems to me to be learning the difference between how to think during practice and how to think during performance. Like Glenn, I read the advice of well-known tennis instructors as a teenager (my favorites were Ed Faulkner, Dennis Van Der Meer, and Billie Jean King); all of these talked about the importance of thinking consciously about the mechanics of making a shot during practice and not thinking consciously about the mechanics of making a shot during match play (performance, as it were), with one exception: consciously keep your eye on the ball until contact with the racket. During match play, the proper substitute for thinking consciously about the mechanics of making a shot was imagining the ball landing perfectly in your opponent's court.

When I perform, I do a lot of thinking: I imagine the desired sound before it happens, I close my eyes and follow the sheet music in my imagination's eye, or I meditate on the word "forgive"; I try my best to minimize thinking consciously about the mechanics of playing during performance, but I think consciously about the mechanics of playing a lot during practice, and I practice a lot. :-)

Evan Marshall