Robin Bullock Discography

Robin Bullock Web site

Robin Bullock and Michel Sikiotakis Web Site

CoMando Guest of the Week

Children's Mandolin Roundtable

Instruments

A-Style Mandolin

F-Style Mandolin

Mandola and Mandocello

Vintage Dealer's Roundtable

Saturday Morning Luthier's Corner

Mandolin Builder's Super Summit

The Virzi Vortex

Mandolin Buyer's Guide

Music Apps

The Genius of Lloyd Loar

Mandozine Gallery

Vintage Grass Valley Photos

Articles

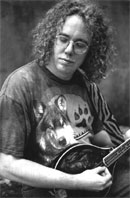

Robin Bullock

Celtic/American "string wizard" Robin Bullock is a prolific composer, respected instructor and workshop leader, and virtuoso multi-instrumentalist, specializing in 6- and 12-string guitars, Irish bouzouki, mandolin, piano and bass guitar. A founding member of the innovative acoustic world-music trio Helicon (winners of the Association for Independent Music's prestigious INDIE Award for their Dorian CD A Winter Solstice With Helicon) and an alumnus of trailblazing Celtic groups The John Whelan Band and Greenfire, Robin has toured extensively throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe and appeared on over two dozen CDs. His own critically acclaimed recorded work includes three CDs on Dorian, Green Fields, the holiday CD A Midnight Clear (on which he alternates tracks with fellow INDIE winners Al Petteway and Amy White), and the soon to be released The Lightning Field, as well as Midnight Howl and Between Earth and Sky on the Maggie's Music label, Travellers with legendary bluegrass mandolinists Butch Baldassari and John Reischman on SoundArt Recordings, and Celtic Guitar Summit with California fingerstylist Steve Baughman on Solid Air Records. Robin's further credits include three Washington Area Music Association WAMMIE Awards, a Governor's Award from the Maryland State Arts Council, and a feature broadcast on National Public Radio's hugely popular Celtic music program The Thistle and Shamrock.

Celtic/American "string wizard" Robin Bullock is a prolific composer, respected instructor and workshop leader, and virtuoso multi-instrumentalist, specializing in 6- and 12-string guitars, Irish bouzouki, mandolin, piano and bass guitar. A founding member of the innovative acoustic world-music trio Helicon (winners of the Association for Independent Music's prestigious INDIE Award for their Dorian CD A Winter Solstice With Helicon) and an alumnus of trailblazing Celtic groups The John Whelan Band and Greenfire, Robin has toured extensively throughout the U.S., Canada and Europe and appeared on over two dozen CDs. His own critically acclaimed recorded work includes three CDs on Dorian, Green Fields, the holiday CD A Midnight Clear (on which he alternates tracks with fellow INDIE winners Al Petteway and Amy White), and the soon to be released The Lightning Field, as well as Midnight Howl and Between Earth and Sky on the Maggie's Music label, Travellers with legendary bluegrass mandolinists Butch Baldassari and John Reischman on SoundArt Recordings, and Celtic Guitar Summit with California fingerstylist Steve Baughman on Solid Air Records. Robin's further credits include three Washington Area Music Association WAMMIE Awards, a Governor's Award from the Maryland State Arts Council, and a feature broadcast on National Public Radio's hugely popular Celtic music program The Thistle and Shamrock.

Born in 1964 in Washington DC, a major focal point for both bluegrass and Irish music, Robin began playing guitar at age seven, initially inspired by Doc and Merle Watson, Norman Blake and John Fahey. Robin's apprenticeship years were spent at fiddlers' conventions, bluegrass festivals and Irish sessions, mastering the subtleties of a half-dozen instruments in both American and Celtic styles. Today, Robin is recognized as one of the few musicians who can so successfully blend the ancient airs and dance tunes of the Celtic lands with the roots music traditions of the "New World."

In 2000, Robin relocated to France, and now lives in the tiny village of Tripleval, on the Seine river northwest of Paris. He continues to tour and record on both sides of the Atlantic, in a number of contexts: solo, in duos with flutist Michel Sikiotakis and guitarist Steve Baughman, and the annual "Winter Celebration" concert tour with Al Petteway and Amy White.

Whether flying solo or soaring with others, Bullock has an extraordinary command of timbre and dynamics...It's easy to overlook his brilliant technique, since it's always in service of the music. - Guitar Player

A musician whose technical skill and stylistic expertise are second to none...a time-served folkie of the highest calibre. - Classical Guitar (U.K.)

Celtic guitar god. - Baltimore City Paper

Q1

Q - Robin, one of my all time favorite recordings is your CD with Butch Baldassari and John Reischman, "Travelers". It is awesome. Any plans to do another?

A - Glad you like it! It's one of my favorites as well, and was great fun to do. I'd love to do a Volume 2, but I don't know that it'll be anytime soon... the three of us are pretty spread out geographically (Vancouver, Nashville and France) so it isn't very feasible to perform together as a trio, much as we'd all like to. (We've played in public exactly twice, both times at Kamp Kaufman!) And since live performances and CD sales sort of feed each other in this business, I'm not sure how practical the investment into a Volume 2 would be. But nothing's impossible!

In the meantime, there are a few live Butch-&-Robin tracks on Steve Kaufman's "Best of the Kamp Koncert Series Volume 4", and a John-&-Robin track on "Best of the Kamp Koncert Series Volume 1", if you want to be a completist... :)

Q2

Q - I use a three finger grip like yourself on the mandolin, and i find it's easier to go through the strings and keep the wrist flexible. My question is what caused you to go to a three finger grip and what pick do you use, also do you use a three finger grip on the guitar and what pick also...thanks

A - Nothing really caused me to "go to" a three finger

grip...it just sort of happened. I played guitar

fingerstyle before I learned about flatpicking on

guitar or mandolin, and I suppose the 3-finger grip is

what happened naturally when I first picked up a pick.

It wasn't until much later that I found out I was in

the minority among flatpickers and mandolinists, but

the 3-finger grip works for me and the conventional

2-finger grip doesn't as well (I've tried), so I guess

I've just never felt any particular need to change!

I also anchor my little finger on the top of the

mandolin, which a lot of people consider heresy, but

again, it works for me. It would probably be best if I

could play without anchoring any part of the hand, but

I've tried that too and it doesn't give me the power

and control I want...I feel a need for some contact

with the instrument, and I never liked anchoring my

wrist or palm because that limits where I can attack

the string. (You get different tone depending on where

along the string you pick...basic string instrument

physics. Fun to experiment with.) So there I am with

my 3-finger grip and my little finger anchored on the

top...there are plenty of mandolin and guitar teachers

who would scream in outrage at that, but I consider it

correct technique _for me_ because it allows me to do

what I want to do comfortably, which is the whole

point of technique. Most people do it differently, I

suppose, and that's fine too. There's more than one

"correct" technique!

(The only caution I would throw in, if you anchor your

finger like me, is to do so VERY VERY LIGHTLY...never

dig in or lean on it, because I use to do that, and

wound up with an inflamed nerve in my little finger

some years ago. As soon as I lightened the anchor, the

problem went away. So learn from my experience. :) )

To answer your other question, yes, I use the same

pick (Gibson jazz heavy, which Barry Mitterhoff turned

me on to), pick grip, and right hand technique on

mandolin, bouzouki, guitar, and even electric bass.

The only difference is that on mandolin I pick with

the rounded shoulder of the pick to cut the trebliness

of the instrument and bring out the mellowness, and on

the other instruments I pick with the point for

clarity and definition.

Q3

Q - I met you at the first Kaufman Kamp in 1999. I am sure you will remember! :-) Seriously, my question is, will you be planning any trips to the West Coast, preferably the Los Angeles, area in the near future?

A - At the moment I've got a northern California mini-tour

shaping up for mid-October with Steve Baughman, a

wonderful fingerstyle Celtic guitarist who's one of my

two present duo partners (the other being the French

Irish flute champion Michel Sikiotakis). Steve and I

will be at the Freight and Salvage in Berkeley on

Thursday October 16th, with other dates in that

general neck of the woods that weekend. Nothing around

LA, though, I'm afraid (though I'm always open to

suggestions for good gigs...if you have any ideas for

places for us to play, do let me know!). Michel and I

are looking at coming out west too, probably next

March, so check in on the website from time to

time...anything's possible.

Q4

Q - At Kamp you did a session on altered tunings for mandolin; really a good intro to the different options. Are you using other tunings much or do you typically stay in standard? Also at that session you did a song, The Golden Vanity, which was fantastic- simple but very beautiful and moving. Any plans to record that? Thanks.

A - I'd been using altered tunings for years on guitar,

but it never really occurred to me to investigate the

idea on mandolin. We have Steve Kaufman to blame for

this :) ...one year at Kamp all of the teachers were

asked to teach two "class scrambles" on a topic of our

choice. The only thing I could think of, besides some

sort of "Intro to Celtic", was a class on altered

tunings. Then I realized: there's the Monroe "Get Up

John" tuning, and his "Last Days on Earth" tuning, and

those are the only two I know, and that'll take maybe

ten minutes, and then what? :)

And that's when it hit me: the mandolin is tuned the

same way as a violin, and I'd been hanging out with

old-time fiddlers who use altered tunings all the

time, so I tried some of those fiddle tunings on the

mandolin, and a whole world opened up. Playing

old-time fiddle tunes on the mandolin using the

traditional tuning for that tune can give you a HUGE

sound, and it's great for playing solo, which I do a

lot. (I've seen Mike Seeger do this in solo concert

too.)

A few of my favorites are GDGD ("Boatman", "Stay All

Night", "Foxhunter's Reel"), GDGB ("Jack o'Diamonds",

"Lost Child", "Black Mountain Rag") and DDAD

("Coleman's March", "Bonaparte's Retreat")...in fact,

I've already used this last tuning on a recording,

"The First Noel/Good King Wenceslas" on the Christmas

CD A Midnight Clear. No doubt there'll be more soon

enough! The two G tunings are also used on the fiddle

in the key of A (i.e. AEAE and AEAC#), but I don't

want to tune mandolin strings above standard pitch, so

if I want those tunings in those keys I use a capo.

Yes, that's right: I use a capo on the mandolin and

I'm not afraid to say it. :) After all, the whole

point of open tunings is the ringing sustain of open

strings, so the conventional prohibition of capo use

on the mandolin no longer applies in that case, it

seems to me. (How did that get started, anyway?)

So far, about all I've done with altered tunings on

the mandolin is this sort of old-time fiddle-inspired

thing...Radim Zenkl, for example, has taken it much

farther than I have. But it's a lot of fun, and yes,

I'm performing in altered tunings more and more all

the time.

As for "The Golden Vanity", well thanks, I'm glad you

liked that! I do that in the key of D with the

mandolin tuned GDAD, a sort-of-standard sort-of-open

tuning that's the primary tuning I use on the cittern.

That's something else that I probably wouldn't have

thought to do if it hadn't been for the Kamp Kaufman

workshop. I got the melody from the incredible Maine

folksinger Gordon Bok, raised it QUITE a few keys to

suit my voice (Bok is a mega-powerhouse bass), and

discovered that the starkness of solo mandolin in that

tuning suited the song perfectly. I haven't recorded

it yet, or any other vocals for that matter, but we'll

see, we'll see...!

Q5

Q - Robin, I was fortunate to have seen Helicon several

years ago at Beserkley's Freight & Salvage. I was very

impressed with your rhythm playing and talked with you

about it during the break. Any tips on rhythm playing

for some of the odd time signatures? And could you

talk a bit about that band, how you met Chris Norman,

& Ken Kolodner. You all made some interesting music

together, I enjoy several of the CD's.

A - I already owned a copy of Chris Norman and Ken

Kolodner's duo album "Daybreak" when I met them at the

Deer Creek Fiddlers' Convention in 1986. They were

looking for a permanent guitar player and I was

looking for a band, and so it began. We took the name

Helicon from the mountain in Greek mythology that was

believed to be the source of all artistic inspiration.

At first we mostly played traditional Celtic and

old-time music, but pretty soon we discovered that

traditional dance music from other parts of the world

suited our instrumentation of wooden flute, hammered

dulcimer, and guitar or cittern equally well. So,

after a few years our concert repertoire consisted

primarily of tunes from South America, eastern Europe,

Scandinavia, China, with the occasional Celtic or

old-time tune thrown in to remind us where we came

from.

Quite a few of those tunes were in what we Yanks would

consider odd time signatures, particularly the tunes

from central and eastern Europe. I actually started it

by contributing a tune in 5/4, "The Storm Warning", to

our second album, but after that the odd-time

floodgates burst and pretty soon we were playing tunes

in 7/8, 14/16, 15/8, all over the place. This probably

sounds terrifying if you've never been exposed to it,

but the way I deal with odd meters is simply to reduce

each measure to combinations of 2's and 3's. For

example, a measure of a tune in 7 will almost always

break down into 2, 2, 3 (counted like this: 1-2 1-2

1-2-3 / 1-2 1-2 1-2-3) or 3, 2, 2 (1-2-3 1-2 1-2 /

1-2-3 1-2 1-2). The first will be perceived by the

listener as short, short, long / short, short, long,

and the second as long, short, short / long, short,

short. Both of which are pretty natural-feeling once

you get used to them...after all, this is a very

common dance rhythm in Greece and elsewhere in that

part of the world. It wouldn't have gotten that way if

it was hard to dance to! By the same token, a "5"

rhythm is either 2, 3 (short, long) or 3, 2 (long,

short), depending on where the melody wants the stress

to be placed. BTW, one of my favorite recordings of

tunes in "odd" meters is "East Wind" by Andy Irvine

and Davy Spillane...Irish musicians playing eastern

European dance tunes. Nothing in 4/4, 3/4 or 6/8 on

the whole CD. Lovely stuff...

Probably the high point of Helicon's time together was

being the first American group invited to perform at

the International Hackbrett (hammered dulcimer)

Festival in Munich, Germany in '93. We thought we knew

what a hammered dulcimer was capable of, but when we

heard great players from China, the Ukraine, Iran,

Switzerland and Romania we knew the bar had just been

raised about a million miles. Unbelievable. We had a

lot of fun as a group, and did a LOT of touring from

'86 to '98...(my favorite Helicon story is the time we

vandalized a gas station after they tried to defraud

us, but that's a story for another day...) :)

Helicon went into indefinite hiatus in 1998. At that

time, Chris was on the road with both the Baltimore

Consort and Skyedance, I was on the road with both

Footworks and the John Whelan Band, and Ken decided he

needed to spend more time at home with his family, so

we just sort of let it go and moved on. Now we play

together only once a year, our annual Winter Solstice

Concert at Meyerhoff Symphony Hall in Baltimore. (We

did manage to get it together long enough to record

one more CD in '99, "A Winter Solstice with

Helicon"...which went on to win an INDIE Award for

Best Seasonal Recording.) These days Chris has his own

group, the Chris Norman Ensemble, and runs Boxwood, a

flute camp in Nova Scotia; Ken plays solo and with

Laura Risk, and teaches a lot; and I'm playing solo

and in duos with Steve Baughman and Michel Sikiotakis.

Our CDs are still out there, though...all but our

first are on Dorian and are available at

http://www.dorian.com.

Glad you both got to hear the group while it was

active...we haven't any plans to revive it at the

moment, but "never say never"!

Q6

Q - Hearing you and citternist Joseph Sobel jam on the last night of Kaufman's Kamp (02), it would be a good guess that you listened to and studied the playing of Andy Irvine. How much of an influence was he? What would you say are the unique aspects and/or innovations o Irvine's mandolin/mandola playing?

A - Andy's mandolin, mandola and bouzouki playing have

been a huge influence either directly or indirectly on

just about everybody in the present-day Irish music

scene, myself included. He was one of the first to

introduce the bouzouki to Irish music (along with

Johnny Moynihan and Donal Lunny), and his and Lunny's

arrangement ideas, with mando-instruments weaving

layers of countermelodies behind vocals or lead

instruments, made Planxty a revolutionary force in the

music 30 years ago. You can still hear what they

started in the work of countless other artists. So

yes, I would say he was a big influence on my work,

although probably less his actual playing than his

ensemble concepts.

I got to meet him a few years back while on the road

in Germany with a Baltimore-based Irish band called

Dogs Among The Bushes...we were playing at the Leipzig

Irish Festival (really!) and Andy was on right before

us. So of course we were joking about Andy Irvine

opening for us...We got to chat with him backstage for

a few minutes; he was a lovely guy and we had a good

time comparing our Sobells. :)

Q7

Q - Here's a "Coffee Talk" topic

A - I'm not as familiar with Mick Moloney's work as I am

with Andy's, but it seems to me that Andy focuses on

the mandolin more as an accompaniment/countermelody

instrument, and Mick more as a melody instrument for

tunes (if he wants to play accompaniment he switches

to guitar). So it's kind of comparing apples and

oranges. Both great players though. In the Celtic

mando world, I've been thoroughly impressed with what

I've heard by Simon Mayor and Chris Newman, Dave

Richardson of Boys of the Lough is an old favorite,

and of course Seamus Egan is brilliant on mandolin as

on everything else he plays. Other than that, though,

I don't think I've really been influenced by that many

mandolin players in the Celtic world...I tend to get

my inspiration and ideas more from players of other

instruments, especially fiddle and flute, and to a

lesser degree pipes, accordion, concertina, whistle

and tenor banjo. Some of my favorite Irish fiddlers

are Kevin Burke, Martin Hayes and Liz Knowles; on

Scottish fiddle Alasdair Fraser, Johnny Cunningham,

Elke Baker and Laura Risk; and on flute Matt Molloy,

Grey Larsen, Cathal McConnell and Michel Sikiotakis

(bien sur!) All of these folks play with the kind of

lift, groove and tone that I strive for in my own

playing.

Q8

Q - Do you also play fingerstyle on guitar? Fingerstyle on bouzouki or mandolin? Pick+fingers? Why or why not?

A - I play guitar both flatpicking and fingerstyle, but

I've never really gotten very far with playing

bouzouki or mandolin fingerstyle. I think it's because

I tend toward alternating bass patterns in my guitar

fingerpicking, which implies at least three bass

strings for the thumb to move around on plus a

sufficient number of strings on top to keep the

fingers happy, so a four-course instrument feels a bit

restricted for that. (Joseph Sobol can get away with

it because he plays 5- and 6-course instruments.)

Q9

Q - Where in France do you live? Have you connected with the French trad. folk, folk-rock scene, and played much of that music? Any recommendations for listening? (aside from Gabriel Yacoub and Malicorne).

A - I live in a village called Tripleval, which is so

small you'll only find it on the most detailed maps of

France...it's about 60 km northwest of Paris, right on

the Seine, and about 5 minutes from Giverny, where

Monet lived and painted. I'm sorry to say that I

haven't really connected with the French trad music

scene at all, other than my partnership with Michel

Sikiotakis, and that's Irish music anyway. I've met a

number of musicians but haven't made much headway into

that scene. I suppose it's partly because my French is

so bad :) , but it's also partly because there's not

much of a trad music scene right around Paris, and

partly because I focus my energies on my trips to the

states, where the kinds of music I'm into are alive

and well.

Q10

Q - Robin, I enjoy your playing very much (and your

teaching...I had you for several workshops at both

Cooks Forest in Pennsylvania and at Kamp). Anyway,

I had a question about learning more than one musical

style.

Most of your music leans to Celtic-styles but if I

recall things I've read correctly you started playing

music as a bluegrass musician and that you also play

old-time music?

How did you make the transition to another style and

did you have to stop playing one kind of music and

immerse yourself exclusively in the new style?

The reason I'm asking is that I don't hear many

vestiges of bluegrass in your playing now. Or even

old-time for that matter. Although I hear more

old-time/Celtic blend on Midnight Howl, but that's the

sound you were going for on that album if I recall.

A - I currently play (or try to play) several styles as I

find so many musical styles so interesting. But my own

personal sound seems kind of strange now because I

keep switching so much and so frequently.

What is the best way to learn more than one style? How

did you do it (or were you able to)? I think you can

because I remember you jamming some great breaks on

some bluegrass down at Kamp a few years ago. :-)

Q11

Q - Do you find it dificult changing instruments and styles. I've seen you perform and you make it look so easy.

A - I don't see that there's any reason why a musician

shouldn't play and enjoy more than one style of music.

Having said that, I think it's important that, if the

style is at all tradition-based (which most are), one

spend time immersing oneself in the style to get a

handle on the tradition, the standards, the fine

points of style and interpretation...learning the

language, if you like. And this requires a certain

humility, because what works in one style might not be

appropriate in another, and you need to suspend

judgment and learn "how it's done" before you start

adding your own twist to it.

In my case, the first music I was seriously bitten by

was bluegrass, when I was 12 or 13, and I spent years

learning everything I could about it: going to

festivals, going to concerts, buying records, reading

Frets magazine (RIP), and playing like crazy. That was

when I first started playing mandolin, in fact. By the

time I discovered Irish music, when I was about 18, I

was already playing professional bluegrass gigs, and I

repeated the process with Irish music: going to

sessions, learning tunes, etc etc...scarfing up all

the information I could. Fortunately for me,

Washington was a really good place to learn both

styles of music, because it had (and still has) very

strong bluegrass and Irish music scenes. Old-time

music showed up in there somewhere, probably the first

time I heard the New Lost City Ramblers, but the line

separating that from bluegrass has never been as

distinct in my mind as a lot of people seem to think

it is... If I haven't as much of a track record in

bluegrass as in Celtic music these days, it's probably

just because I haven't had much of a performance

outlet for bluegrass in recent years. My first

full-time gig, three weeks after graduating from high

school, was playing mandolin six days a week in the

house bluegrass band at the Sheraton hotel in

Gatlinburg, Tennessee (the guitar player in that band

was Richard Bennett). I also played mandolin with Bill

Harrell and the Virginians for a brief period in 1988

before my gig schedule with Helicon created too much

of a conflict. So I've done some bluegrass miles! I

suppose I'm "known" for Celtic music in one form or

another as much as anything, but I do think the three

strands of Celtic, bluegrass and old-time show their

influence in everything I do, sometimes more subtly

and sometimes more obviously. "Travellers" was as

close as I've gotten (so far) to a

bluegrass/old-time/Americana sort of recording, and I

loved doing it; I'm sure there are others yet to come!

I don't think there's anything necessarily wrong with

this sort of combining of styles, but I do recommend

keeping in touch with the purer forms of the various

styles you're trying to combine, to keep your own

hybrid from becoming completely schizophrenic. :) I

listen to a lot of "pure drop" Irish music, a lot of

hardcore bluegrass, and a lot of straight old-time

music, and I like to think I can identify what

elements differentiate the three musics...as well as

what their similarities and commonalities are. And if

I break the rules, at least I know that I _am_

breaking the rules, and which ones I'm breaking. :)

But I can also participate in a jam session or a

performance of any of the three and pull it off

completely straight...not because I'm any great

genius, but because I've spent the time hanging out

with all those musics, accepting them on their own

terms and loving them for everything they are. (I also

listen to a lot of Bach and a lot of Grateful

Dead...inspiration is where you find it!)

As for changing instruments, that's easy: you put one

down and pick up another. :) Honestly, I'm not sure

what to say about that, because I've never really

thought about it...I consider the instrument to be the

means to an end, not the end in itself. In other

words, I don't consider myself a guitarist,

mandolinist, or citternist; I consider myself a

musician, and I use several different tools to say

what I want to say. (I also find, in the words of

piper Pat O'Gorman, "we don't choose the instruments

we play, they choose us.") But I think everything I

just said about learning different styles applies to

different instruments as well: to feel comfortable

with any of them, you have to put in the time. On a

purely physical level, I try to remain as loose and

relaxed as I can on any instrument; this helps to

minimize the shock of changing from one neck width to

another (for example). Hope that helps; I'll stop now

before Yahoo truncates this post! :)

Q12

Q - I was lucky enough to be a student at Kamp Kaufman when you were teaching there. You had a concept about the "corners" of a tune. Can you share that with the list.

A - I'll try...it's easier with a mandolin in my hands...

:) The concept and the name "corners" both came from

Ken Kolodner, hammered dulcimer player with Helicon.

He and I both noticed that students trying to learn

fiddle tunes were having a rough time of it learning

them from books, because what they saw there was a

string of eighth notes and, reasonably enough, assumed

that they had to learn every one of those notes and

play them exactly that same way every time. He

decided, and I agree, that it's a mistake to think of

a tune that way, because...BIG SECRET COMING UP...not

all the notes in a fiddle tune melody are equally

important. Some notes define the melody, and some are

only there to fill time between the more important

notes. After all, no two players' versions of a tune

are the same note-for-note...AND YET, there's some

framework common to all of them that allows us to

identify the tune as "Soldier's Joy" or "Salt Creek"

or whatever.

So Ken came up with the idea of the "corners" of a

tune, that is, the notes of a tune that define the

overall shape of the melody. You could also call them

the "skeleton" or the "frame" or whatever you want to

call them, but the idea is, if you play the "corners"

at the right time, or even most of them, then the

notes you insert in between aren't really that

important as long as there're stylistically

appropriate.

For example: the A part of "Whiskey Before Breakfast".

Written in a tunebook might look like this:

| | | | | | | | | | | | |----------------|----------------|------------------| |--------0-------|-0-2-0----------|-----2-------0----| |0-2-4-5-----4-5-|-------5-4-2-0--|-5-----5-4-----4--| |----------------|----------------|------------------| | | | | | | | | | | | | |----------------|-----------------|-----------------| |----------------|---------0-------|-0-2-0-----------| |5-2-4-0-2-0-----|-0-2-4-5-----4-5-|-------5-4-0-2-4-| |------------4-2-|-----------------|-----------------| | | | | | | | | |----------------|---------------| |--0-2-----0-----|---------------| |5-----5-4---5-4-|-2-0-2-4-0-----| |----------------|---------------|

Which is certainly the A part of "Whiskey Before

Breakfast", but it's not the only way of playing it

that will be identifiably "Whiskey Before Breakfast".

Yet it's perfectly understandable that a student faced

with this will assume that a) this is "the" way to

play this tune and I better play it exactly this way,

and b) all these notes are equally important. It's

also understandable that they'd be a bit confused if

they got hold of a recording of someone playing the

tune or heard someone playing it live and tried to

match it up with this written version...odds are that

it would vary considerably, of course. YET IT WOULD

STILL BE "WHISKEY BEFORE BREAKFAST" AND NOT SOME OTHER

TUNE, EVEN THOUGH THE NOTES AREN'T THE SAME!

Why? Because the musician is playing the "corners", or

most of them, and filling in as he or she pleases.

(The farther away one gets from the "corners", the

farther one gets from the tune being identifiable as

what it is, and enters the world of improvisation.)

So what are the "corners"? The "corners" generally

fall on the strong beats and/or at the point of chord

changes...there's no hard and fast rule, you just sort

of know it when you hear it. To continue our example,

the "corners" of WBB might look like this:

| | | | | | | | | | | | |----------------|---------------|-------------------| |--------0-------|-0-------------|-------------------| |0---4-----------|---------4---0-|-5-------4---------| |----------------|---------------|-------------------| | | | | | | | | | | | | |----------------|---------------|-------------------| |----------------|---------0-----|-0-------4---------| |-2--------------|-0---4---------|-------------0-----| |----------------|---------------|-------------------| | | | | | | | | |----------------|----------------| |----------------|----------------| |-5-------4------|-2-------0------| |----------------|----------------|

...in other words, a completely bare, stripped-down

approximation of the melody. But you can connect these

notes with any other notes that fit the style of the

tune (in this case, notes from the D major scale) and,

more or less by definition, be playing "Whiskey Before

Breakfast".

The beauty of this approach is that it allows you to

think of a tune as a melodic statement that varies

from player to player while maintaining its basic

identity, rather than as a bunch of notes that are

hard to remember. It also demystifies learning tunes

by ear...when I learn a tune by ear, I listen for the

"corners". It's much faster to listen past the flurry

of melody notes and focus on getting those "corners",

and once I've got them, I've basically got all I need

to play the tune, or something mighty close to it.

Q13

Q - I'd love to hear you talk some about the mechanics of triplets and suggestions for their use in ornamenting tunes. Assume I know nothing (not a hard assumption!).

A - It's one of my most-requested topics as a teacher

because they're used all the time in Irish trad music

(in fact it's a big part of what gives that style its

personality), but you virtually never encounter them

in bluegrass or old-time. I personally prefer the term

"rolls", because they're not always triplets, strictly

speaking...

Rolls are those percussive flurries that drive along

dance tunes like reels and jigs. They're played on all

the traditional melody instruments in Irish music,

fiddle, flute, whistle, pipes, accordion, concertina,

tenor banjo, mandolin and even Celtic harp. But since

these instruments cover several different instrument

families, they all execute rolls slightly differently.

A flute player, for instance, creates the percussive

sound of a roll by quickly raising and lowering a

couple of fingers in quick succession, thus breaking

up the note the roll is ornamenting without allowing

the other notes to be perceived by the ear as

notes...more as stoppages of the main note. (With me

so far?) A button accordion player, on the other hand,

creates a roll by sliding three fingers down the same

button, causing the same note to sound several times.

A fiddler has the option of flicking a couple of extra

notes with the left hand on a continuous bow stroke,

or stopping and starting the bow with a flick of the

right wrist. So it's not really the notes that are

important, since they vary from instrument to

instrument; it's the percussive effect. Ideally, you

shouldn't really hear the notes in the roll, you

should just hear the roll itself as a percussive

augmentation of the melody.

The way I do that on mandolin is indeed a triplet...if

I'm playing a tune in 4/4, such as a reel. Generally

rolls are inserted at a point where the melody either

sustains one note or has the same note several times

in a row. Irish musicians consider this melodically

static, and break it up with a roll. For example, take

the first two measures of "Miss MacLeod's Reel":

| | | | | | | | |-----------------|-----------------| |---0-2-3-5-2---0-|-2---2-0-2-3-2-0-| |-5-----------5---|-----------------| |-----------------|-----------------|

At the beginning of the second measure, the melody hangs on a B note for a beat and a half. So I might choose to break that up with a roll, and I would do so by breaking the quarter note into three evenly-spaced notes (a triplet):

| | | | | (3) | | | |-----------------|-------------------| |---0-2-3-5-2---0-|-0-2-2-2-0-2-3-2-0-| |-5-----------5---|-------------------| |-----------------|-------------------|

Now...assuming we're playing downstrokes on the beats

and upstrokes on the notes between beats (DUDUDUDU),

which is a hard and fast rule 99.9% of the time, how

do we play three notes in the space of two? By playing

them down-up-down, and (here's the secret) the next

two up-up. I do it this way because up to speed

there's no time to correct for the extra note either

within the triplet or going from the triplet into the

next "straight" melody note, but there IS time (just!)

to make the correction with two strokes in the same

direction right after that, hence two upstrokes...and

you're back on solid DUDU ground in time for the next

beat.

The other thing to remember is that a roll is an

ornament...it's not the melody itself. So I would play

that triplet as lightly as possible, aiming for the

notes to sound more percussive than notelike, and then

I would accent the note that follows. (Yes, that would

be the one on the upstroke...sorry about that.) This

is all intended to help give the tune that undefinable

yet indispensable quality known as "lift"...that which

causes you to tap your feet and feel like dancing. Two

of my favorite Irish musicians for "lift" are fiddler

Kevin Burke and button accordionist Joe Burke (maybe

there's something about the name Burke that gives you

lift...as far as I know they're not related). But you

can probably get a feel for where to insert rolls into

a tune from listening to any Irish melody instrument

players.

I'd love to hear more folks do this in bluegrass and

old-time...I threw in a few rolls here and there in my

melody sections of the "Travellers" CD, just to see

how they'd sound in a basically American repertoire,

and it worked for me! :)

Q14

Q - Is there a songbook or instructional method that you have found particularly useful over the years?

A - Honestly, I've been pretty out of touch with the

instructional method scene since I left my old job at

Baltimore Bluegrass years ago...there's a world of

stuff out there, and I really don't know which

specific books or videos to recommend, but there are

certain publishers whose stuff seems to be

consistently good, such as Oak Publications, Homespun,

anything by Steve Kaufman, and I'll probably think of

lots more as soon as I post this...

Anyway, there's nothing like studying with a live

teacher, or just hanging out with a musician you

respect even if it's not a formal teacher-student

relationship. (A great way to have a concentrated dose

of that is to attend a camp such as Kamp Kaufman, the

Swannanoa Gathering, Common Ground on the Hill or

Augusta.) The next best thing, I would think, would be

video methods, where you can at least see and hear

what's going on, and after that good books, preferably

those with recordings included.

For repertoire, the Fiddler's Fakebook is excellent

for a broad cross-section of standard tunes from

bluegrass, old-time, Irish, Scottish, Shetland, New

England, etc etc. It's in standard notation only;

there's also a Mandolin Picker's Fakebook that's

basically the same book in mandolin tab.

Q15

Q - What is the best way of inserting your own triplets into a tune? Is there is a certain place in the measure that they tend to fall on?

A - I talked about triplets in another post, so have a

look at that, but briefly, triplets tend to come when

the melody consists of one long note or several of the

same note. In Irish music, that's considered

melodically static, so a triplet or roll is inserted

to break it up and keep things moving along. The best

way to get a feel for where to insert triplets is to

listen to as much trad Irish music as you can get your

hands on, particularly recordings with only one or two

melody instruments and light backup so you can really

hear what's happening. (A good place to start: "Kevin

Burke in Concert" on Green Linnet. Magnificent solo

fiddle. I'd like to play the mandolin like he plays

the fiddle.)

Q16

Q - Way back when at the first Kaufman Kamp your were playing a blonde Washburn mandolin. Do you still play that one?

A - No, I bought a Weber Beartooth a couple of years ago

and promptly sold the Washburn to my website designer,

Jerry Garland. It actually wasn't a bad recording

mandolin, but wasn't really what I wanted for

performing, and I just never got around to upgrading

for a long time because I was playing in bands where I

didn't play mandolin (Helicon, the John Whelan Band,

Greenfire). But John Bird alerted me to a sale on

Mandolin Cafe (thanks, John!), and I wound up with the

Weber and am really enjoying it. I even got to meet

Bruce Weber at Kaufman Kamp right after I got it, and

I can personally testify that he's a hell of a nice

guy.

Q17

Q - What do you look for in a mandolin for the Celtic style of music.

A - Most of the time Celtic mandolin players are looking

for a ringing sound that's altogether different from

the typical bluegrass mandolin sound...the sort of

sound you'd get from an old Gibson oval-hole A-model

like an A-2 or A-4, or a Sobell oval-hole mandolin, or

even a Flatiron "Army-Navy" model. Way back in '87 or

'88 I bought a cheapo Russian mandolin for $75 at

House of Musical Traditions that just happened to have

that "Celtic" sound, and I've actually used it on a

number of CDs over the years (it's on the opening

track of "The Lightning Field", for instance). But

since I got the Weber I'm finding that it's versatile

enough to handle the different styles I play...it's

got a fine bluegrass sound but it's not as "woody" as,

say, an old F-5, so I can get away with playing Celtic

repertoire on it too.

Q18

Q - Can you expound a bit on playing jigs. Things like pick direction, backing them up for a concert, and backing them up for a dance, etc.

To me, there need to be more drive and rhythm for a dance, so instead of a DUDDUD or DUDUDUD it needs chop type chords and a D-u D-u for each measure.... well I guess more of a d-u D-u, d-u D-u..... where the d on beat 1 is a ringing 3 or 4 string chop chord, - on beat 2 is a rest, the u is a light up stroke on beat 3 and the D on beat 4 is a chopped chop chord, etc. Other chord formations would work, but you need the chopped chord to give some lift. Am I on the right track?

A - First off, for playing the melody, there seem to be

three basic approaches to pick direction for 6/8 (jig)

time: DUD DUD, DUD UDU, and DDU DDU. They all work, in

different ways. DUD DUD and DDU DDU give you a bit

more natural emphasis at the beginning of the second

group of three notes, since you're playing a

downstroke there which is easier to emphasize, but DUD

UDU involves less physical work, which appeals to me.

:) It _is_ possible, despite what you'll hear some

people say, to get a convincing jig feel using this

method...it just means you have to learn to emphasize

the upstroke when you need to, which is a good skill

to have anyway. Myself, I mostly use DUD UDU, but

throw in DUD DUD once in a while too. I've never been

able to get the hang of DDU DDU, so I don't bother

with it, but there are players that it works fine for.

Vive la difference.

As for backing...I hardly ever back up jigs on the

mandolin. Mandolin in Celtic music is almost always

used as a melody instrument, at least on dance tunes.

I do back jigs on guitar and bouzouki though, using

the same pick directions as when I play melody, and my

basic approach is lots of ringing open strings and the

principle emphases coming on 1 and 4 (counting a jig

1-2-3 4-5-6 for the moment, to make this easier to put

into words). If I'm emphasizing 1 and 4, I then play

fairly small, ringing chords on 3 and 6, and nothing

or virtually nothing on 2 and 5. However, once that

basic pattern is up and running, I immediately start

messing with it :) by moving emphasis from 4 to 3 and

back again, to give the tune a kick. In other words,

it's either ONE (two) three FOUR (five) six, or ONE

(two) THREE (four) (five) six. Randomly back and forth

between those two. If I want a smaller, more intimate

sound, then I pick individual strings within the chord

instead of strumming the whole chord, playing a bass

note on the "one", but I use the same rhythmic

patterns. That's the basics...

To back a jig on the mandolin, you could try it that

way, using open chord positions...it's just my

personal opinion, but I feel like chop chord

accompaniment on jigs doesn't sound very Irish. Of

course, it depends what sound you're going for...it

might work just fine for more of a New England contra

dance sound. It's true that piano players in Irish

ceili bands tend to play bass notes on 1 and 4 and

staccato chords on 3 and 6, but for some reason that

doesn't seem to translate to the mandolin that well.

JMHO, YMMV!

Q19

Q - Robin, I don't know if you normally give lessons, but do you have any suggested practise regimens for different stages of development (however you define these), e.g., advanced novice, low intermediate, high intermediate, etc.?

A - I used to teach privately quite a lot, and still do

group workshops in the summer at camps like Common

Ground on the Hill and the Swannanoa Gathering (plug!

plug! :) ...http://www.commongroundonthehill.com,

http://www.swangathering.com ), and of course Kamp

Kaufman now and then...I've no particular practice

regimen, rather I generally make it up for each

individual based on what they want to achieve and what

I think they need. But in general, I recommend warming

up on your instrument by playing something easy and

slow to get the blood flowing and allow those small

muscles to stretch in a healthy way, just like an

athlete stretching.

After that, the best advice I ever heard about the art

of practicing came from Dan Crary at one of the

Kaufman flatpick camps, so I'll share that with you as

best I remember it:

SET A SPECIFIC GOAL THAT CAN BE ACHIEVED IN THIS PRACTICE PERIOD. Not something vague and long-term like "I want to play like Sam Bush someday", but something that you have a real chance at mastering during _this_ practice period, like "I will be able to play cleanly that passage in the A part of Arkansas Traveler that I always crash on."

IF YOU'RE HALFWAY THROUGH YOUR PRACTICE PERIOD AND IT BECOMES APPARENT THAT YOU'RE NOT GOING TO REACH THAT GOAL, CUT IT IN HALF. Make it just the first measure of that problem passage, for instance. The idea here is that you want to succeed at reaching a goal every time you practice.

ALLOW YOURSELF A SUCCESS EVERY TIME YOU PRACTICE. Positive reinforcement. And an important part of that is...

SHARE YOUR SUCCESS WITH SOMEBODY. Spouse, bandmate, fellow student, dog, whoever, but Dan's point here was that having a support system in your musical life is very important to keeping your morale up. Tell what you succeeded in accomplishing to somebody who understands the importance of it!

To all of which I would add: practice with a

metronome...yeah, I know, we all hate them, but I'm

here to tell you it'll make a HUGE difference in your

sense of timing before you know it. There are two ways

to play with a metronome: one is to resent it and

fight with it, the other is to surrender to it and

work toward locking in with it effortlessly, so that

you can anticipate when the next click is going to

happen and be right there with it without any tension.

A great way to practice with a metronome that I picked

up from Steve Kaufman is to start with it clicking

deadly slow, and not speed it up until you're

completely comfortable and groovin' with the metronome

there. Then raise the tempo a few notches and repeat

the process, then raise it again, and so on until you

reach your maximum. Great way to build both your speed

and your overall sense of rhythm.

And finally: Play with other people whenever you can,

and have fun!

Q20

Q - With the time you spend in France, Europe etc. what are you impressions of the skill levels and techniques of the European amateur mandolin players as opposed to the amateur mandolin players in the USA. Any difference in numbers of players also. Are better or more instructors available? Do you find the general public more interested and passionate about acoustic music (mandolin) in France as opposed to USA?

A - To be honest I haven't investigated the acoustic music

scene in France outside of the Paris area, but what

I've seen (and what natives have told me) is there

isn't that much of an acoustic music scene here, in

this part of France anyway. There's a weekly bluegrass

jam session and three Irish sessions that I know of in

Paris or the suburbs, but there aren't that many

participants. (The ones that are involved in it, to be

fair, are deeply into it.) And there's no concert or

club scene to speak of...Michel and I wanted to do a

CD release concert in Paris this spring and ultimately

decided not to because there aren't any venues and not

much of a market. Paris is a wonderful city, but it's

not a center for acoustic/trad music particularly.

Although there is a fair amount of gypsy swing...if

you know where to find it...

Elsewhere in Europe it may well be a different story.

I'm told that there's a thriving bluegrass scene in

the Czech Republic, for example, and of course I would

assume that there's mandolin activity in Italy -

that's where the instrument came from, after all!

Haven't been to those countries myself yet, nor have I

made it to EWOB, the annual European World Of

Bluegrass convention. There is a bluegrass scene in

Europe, undoubtedly, just not too much around Paris.

Ireland, of course, is absolutely crawling with music

and musicians, although on my last trip there I didn't

see many mandolin players...but there are boatloads of

great fiddlers, flute players, pipers, accordionists,

bouzouki players, etc. That music is in good hands!

And I'm told that Brittany is a happening scene,

mostly Breton trad music of course, which I'm not as

familiar with, but Michel assures me that there are

some killer Irish players there too. Again, though,

I'm not sure how much of a role the mandolin plays in

that scene...

It may just be tunnel vision on my part, but after

three years here it looks to me like the

folk/trad/acoustic/bluegrass and even Celtic scene is

in as healthy a state in America as anywhere else (and

probably healthier than most places), and that there

are a lot more mandolin players there, both amateur

and professional. Fortunately, I spend several months

of the year on the road in the U.S., so I get my "fix"

then. So, to answer your last question, the players

that _are_ here are certainly passionate, but there

aren't nearly as many of them...where I live, anyway.

Q21

Q - On the guitar, when using pentatonic scales, there are five positions per key and then they (of course) repeat in order up or down. I've drawn out mando blues pentatonic and major pentatonic scales but failed to see any such obvious or connecting patterns covering the entire neck. There are connecting scales but I don't see such a simple way to move up and down the complete nec, using all strings. Right now I know "cross string) octaves and am adding a third up from the second, which seems to always lead you to same the same neighborhood of the key. (I chord in another shap) I'm mostly playing G -B# chop cord based keys) Are they any such patterns on the mando that cover the entire neck? ...this is the sort of info I really need from this list as there are no instructors around here. (I'm not referring to the basic fingering positions as derived from the violin).

A - I'm afraid I'm not following you on most of that.

Maybe it's because I don't usually think in terms of

scales, pentatonic or otherwise, when I'm improvising

up the neck, but rather (I guess) in terms of chord

positions...even two-note chords. (Yes, I know two

notes is only an interval, not a chord, but let's not

split hairs...) For example, if I wanted to go up the

neck on a solo in G major, I might start with the

two-note G "chord" created by the B at the 7th fret of

the 1st string with my 2nd finger and the G at the

10th fret of the 2nd string with my 4th finger. From

that jumping-off point I have easy access to the G

major scale between the 5th and 10th frets if I use

all 4 fingers. But I don't think of it as a scale

shape, I think of it (if I think at all...) as coming

off that two-finger G "chord" on the top two strings.

To learn my way around the neck of the mandolin, I

always played tunes and songs, right from the

beginning...not scale exercises. I've never been much

for scale exercises because that's not what you play

in the real world. If it helps you understand how

things lie on the fingerboard, great, but for me the

time was better spent learning how to play actual

music in unfamiliar positions on the neck, and then

observing and remembering where I found things. For

example, I would set myself challenges like "Play

Sailor's Hornpipe in A without ever going below the

fifth fret." Then: "Do it again in B flat...then in

B..." Torturous, but you emerge from that sort of

thing with both some practical experience of the

fingerboard and a much better instinct for what

positions to use when, in a real tune.

Maybe we're both doing the same thing and verbalizing

it two different ways. I'm not sure. Fortunately, if

all else fails, the mandolin neck is short enough to

make emergency position shifts in midstream if you

need to! :)

Q22

Q - It seems to me that major pentatonic scales automatically give you the "corners" of melodies. Do you agree or am I missing something here?

A - Actually, I don't think that's a safe assumption.

Right off, the tune I used as an example, "Whiskey

Before Breakfast", had G as one of its "corner" notes,

which isn't in the D major pentatonic scale. The D

major scale, yes, but that's a different thing...

Most fiddle tunes tend to be diatonic (i.e. within a

seven-note scale), but only some are truly

pentatonic..."Sandy River Belle" comes to mind...and

"corner" notes can come from anywhere within the scale

the tune is in. Furthermore, when I speak of a

diatonic scale, I don't just mean major...there are

other modes to be considered. (Modes! Oh boy, here we

go!) A tune in the mixolydian mode, for example, could

have corner notes from anywhere in the mixolydian

scale (for the uninitiated, do, re, mi, fa, sol, la,

ti-flat, do). The corner notes might _happen_ to all

fall within the major pentatonic scale, which is

contained in the mixolydian scale, but it would only

be coincidence, not something you want to base your

understanding of the tune around.

To further complicate matters, there are lots of tunes

in the Irish and Scottish traditions in what's called

the "gapped" scale, i.e. the mixolydian mode without a

third (do, re, fa, sol, la, ti-flat, do). This makes

the tune neither major nor minor, strictly speaking.

(Examples: "The Tenpenny Bit", "The Killarney Boys of

Pleasure", "John MacKenzie's Fancy".) A major

pentatonic scale will actually violate the

neither-major-nor-minor-ness of a tune like that, as

one of the five notes in the major pentatonic scale is

the major third, which we're specifically trying to

avoid. And the "corners" of such a tune can be any

notes from the gapped scale, but the major third won't

be one of them in all likelihood.

In short, the major pentatonic scale is useful for

certain things (as is any kind of scale), but it's not

an automatic corner-finder. One tip: corners are

usually on strong beats, and that's where chord

changes are likely to occur too, so notice what the

chord is at any given moment and chances are the

corner there will be one of the notes within that chord.

Q23

Q - What 3 finger grip? Is there a pic of it?

A - I don't have any pics, but it's basically that the

pick is held between the thumb on one side and the

index and middle fingers side-by-side on the other,

forming something of a triangle. All three digits are

in contact with the pick not at the tip exactly, but

between the tip and the pad. Different from the

typical two-finger grip where the index finger is

curved and it's the side of the finger that touches

the pick. As I say, it's a less common approach, but

it works for me...